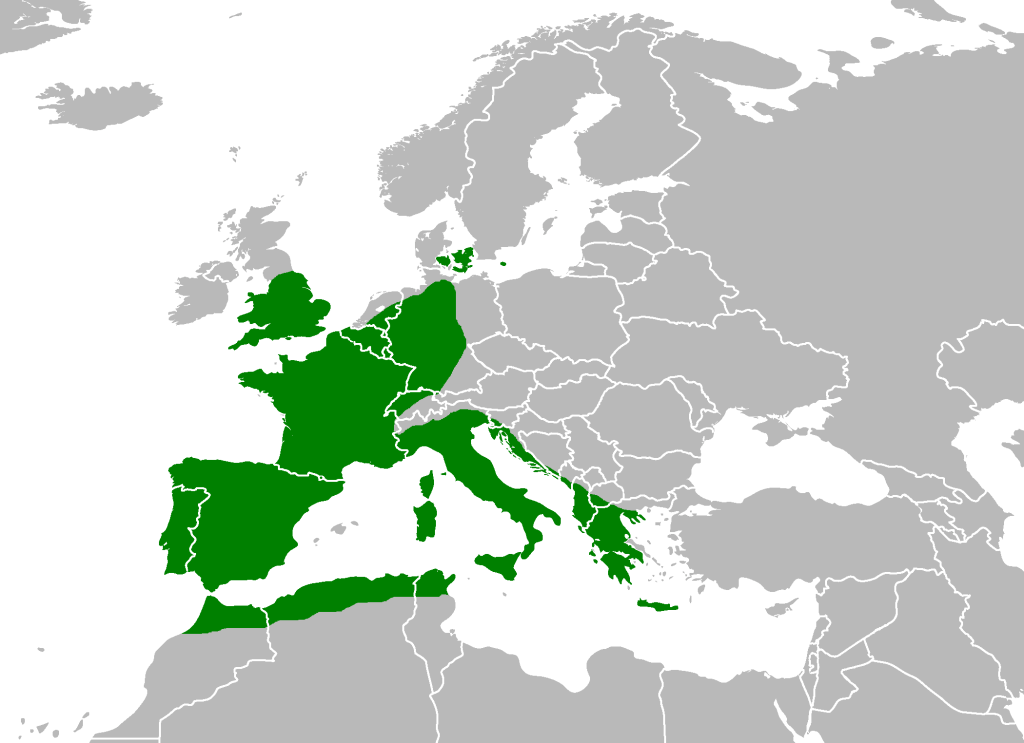

The thick-legged flower beetle, Oedemera nobilis (Family Oedemeridae), is a common pollen-feeding beetle found in flower heads during the spring and summer. They occur throughout western and southern Europe and are known by a variety of alternative names, including false oil beetle or the swollen-thighed beetle.

Xvazquez, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The males have impressively enlarged hind legs, sometimes called ‘saddlebag femora’, and recent research has provided an explanation for the function of these extraordinary adaptations.

The enlarged hind legs (femora) are only found in the males; i.e. a sexually dimorphic feature. When I first drafted this blog in 2018, I could find little or nothing about their function, and I asked: is it possible that they are used by the males during courtship or mating? Or, perhaps in competition with other males, or as an exaggerated feature favoured by females when they choose their mates?

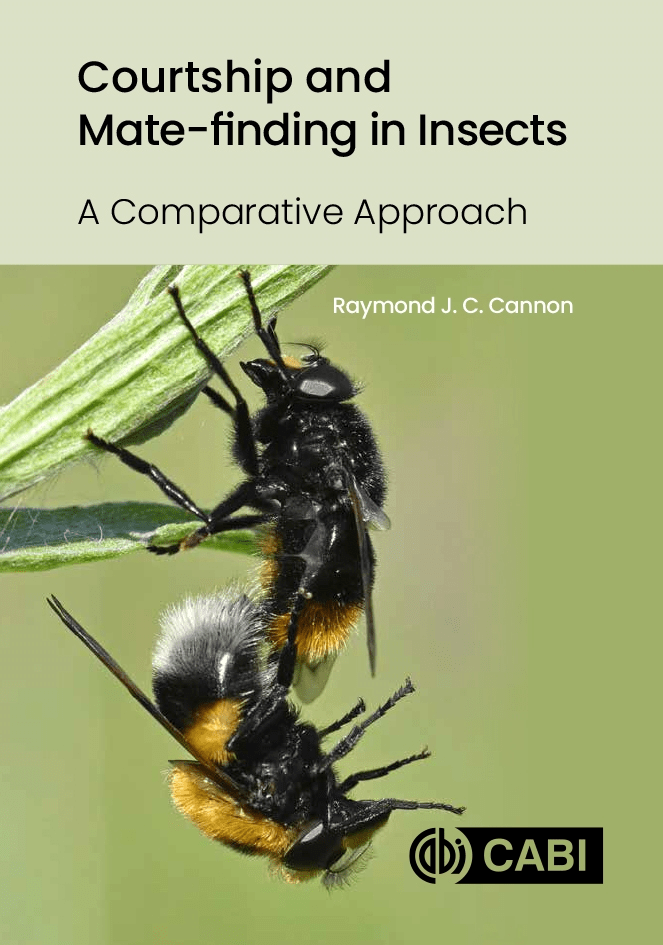

Since then, research by Professor Malcolm Burrows of the University of Cambridge has discovered the purpose of these swollen femora: they have evolved “to grasp a female during mating and to ensure the stability and hence success of the process” (Burrows, 2020). The males grasp the females tightly with their massive femora, in a manner analogous to that of a mole wrench, which allows them to grip on tightly without damaging the females’ abdomens. Something the females will no doubt appreciate!

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

The hind femora of the adult male is 38 times more voluminous greater than that in adult females (Burrows, 2020). However, despite this huge difference in the volume of the hind-leg femora in males, it does not give them much of an advantage in terms of jumping or taking-off, compared with females.

During mating, the males tighten their hind-legs around the middle of the female’s abdomen such that it can become indented (See Fig. 8 in Burrows, 2020). I expect the exoskeleton of these beetles is flexible enough to survive such treatment! This firm grasp on the female by the male, is followed by mating as the male manoeuvres the tip of his abdomen until the two sets of genitalia became engaged in copulation.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

The adults – 8-11mm in length – are quite easy to spot during the summer in open flower heads of many plants, of which they are pollinators, such as cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris), ox-eye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), bramble (Rubus fruticosus), thistles and many other species. The larvae are harder to spot, feeding and developing within the stems of plants such as thistles (Cirsium). One characteristic of this species is that they do not do their jackets up tightly! So to speak. (See below).

In other words, their green elytra (or wing covers) are pointed and gape apart, i.e. they do not meet up properly, especially at the far (distal) end. It is easy to see why they are such good pollinators (below) because they get covered in pollen and move from one flower head to another!

The females lack the thick hind-legs (femora) but are similar in all other respects, apart from the fact that their slim hind-legs are slightly shorter than those of the male (Burrows, 2020).

Whilst photographing these beetles in Spain (Galicia), I came a white crab spider (Misumena vatia) waiting for prey on a thistle head (below).

Suddenly, a Thick-legged flower beetle (Oedemera nobilis) arrived on the thistle and stood right on top of the White crab spider (below). Clearly, it was not the right prey item for the spider. Either it was too large or too difficult to eat? In any case, the crab spider made no move the capture the beetle which wandered about the flower seemingly unconcerned about the presence of a would be predator!

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Crab spiders are certainly capable of taking prey items at least as big as themselves and sometimes larger. There are many images of them (see here) with bees, wasps, butterflies, moths, flies and so on. Perhaps these beetles with their huge back legs are just too strong for them?

Thick-legged flower beetle males are not so tolerant of other males. I was photographing one on another thistle when I witnessed a brief altercation between two males (below). The tussle was very rapid and I only managed to get just one shot.

After the fight the two beetles settled down to feeding on the same flower. Perhaps it was a sort of dominance thing? Sizing up who has the fattest legs! Interestingly, one of the males – the one on the right in the following photo – appears to have slightly thinner hind femora; not so shiny and enlarged. However, Malcolm Burrows (2020) found that in tussles between males, any attempts to by one male to grab and hold of another by using its enlarged hindlegs, are often thwarted by the pursued male extending his hind-legs vertically! Perhaps this raising of the enlarged legs in the air is a submissive gesture?

There is, I suspect, still much to find out about the behaviour of these beetles. The observations by Professor Burrows of behavioural interactions between males and females before and during mating suggests to me that the courtship interactions of this species could be investigated further, and also under field conditions (e.g. see Cannon, 2023).

References

Burrows, M. (2020). Do the enlarged hind legs of male thick-legged flower beetles contribute to take-off or mating?. Journal of Experimental Biology, 223(1), jeb212670. https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article/223/1/jeb212670/224612/Do-the-enlarged-hind-legs-of-male-thick-legged

Cannon, R. J. (2023). Courtship and Mate-finding in Insects: A Comparative Approach. CABI. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/book/10.1079/9781789248623.0000

Knight, K. (2020). Male flower beetles’ massive femora clamp females in place. jeb219428. https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article/223/1/jeb219428/224611/Male-flower-beetles-massive-femora-clamp-females

lovely detailed observations and terrific pics as always Ray, thank you

I have a video captured today of a male attempting to mate with a female. It might give you some insight into the use of the males legs? Let me know if you would like me to send it to you.

Great. I would be interested to see this behaviour. Regards, Ray

Rcannon992@aol.com

[…] We now know, thanks to research by Professor Malcolm Burrows of the University of Cambridge, that these swollen femora have evolved “to grasp a female during mating and to ensure the stability and hence success of the process” (Burrows, 2020). See here. […]