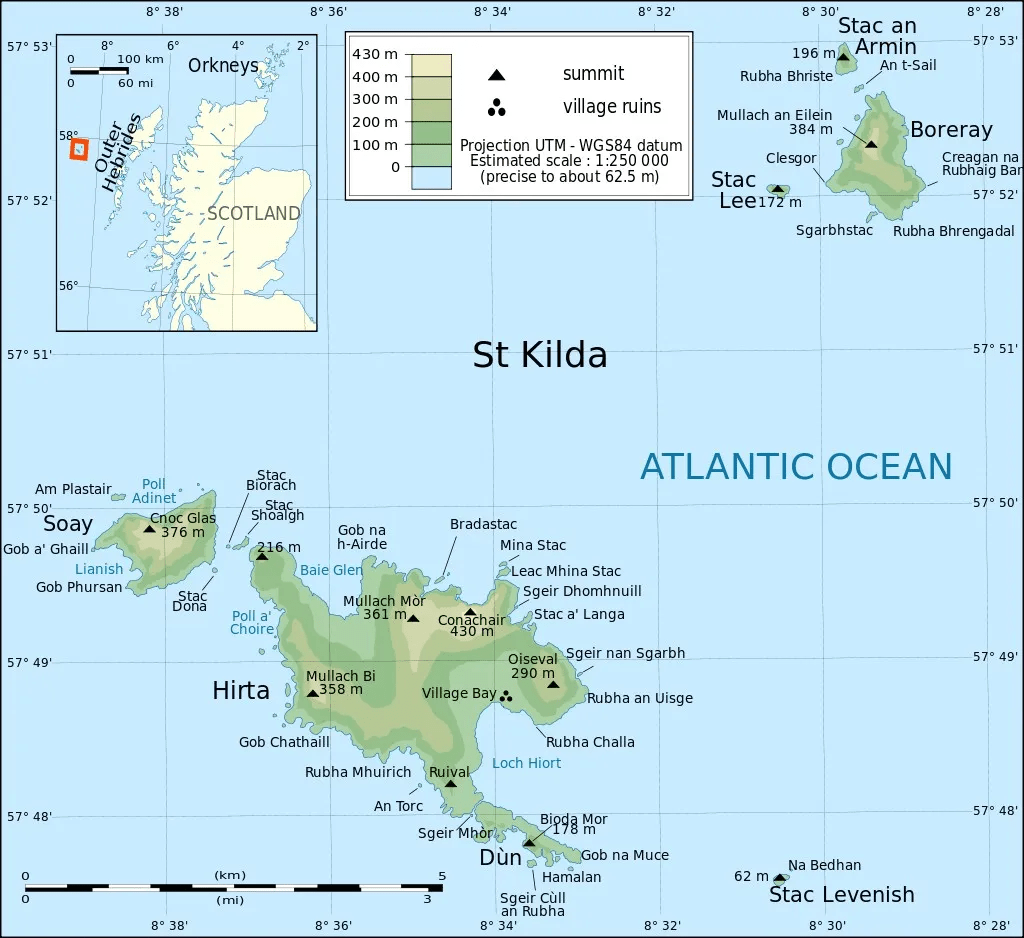

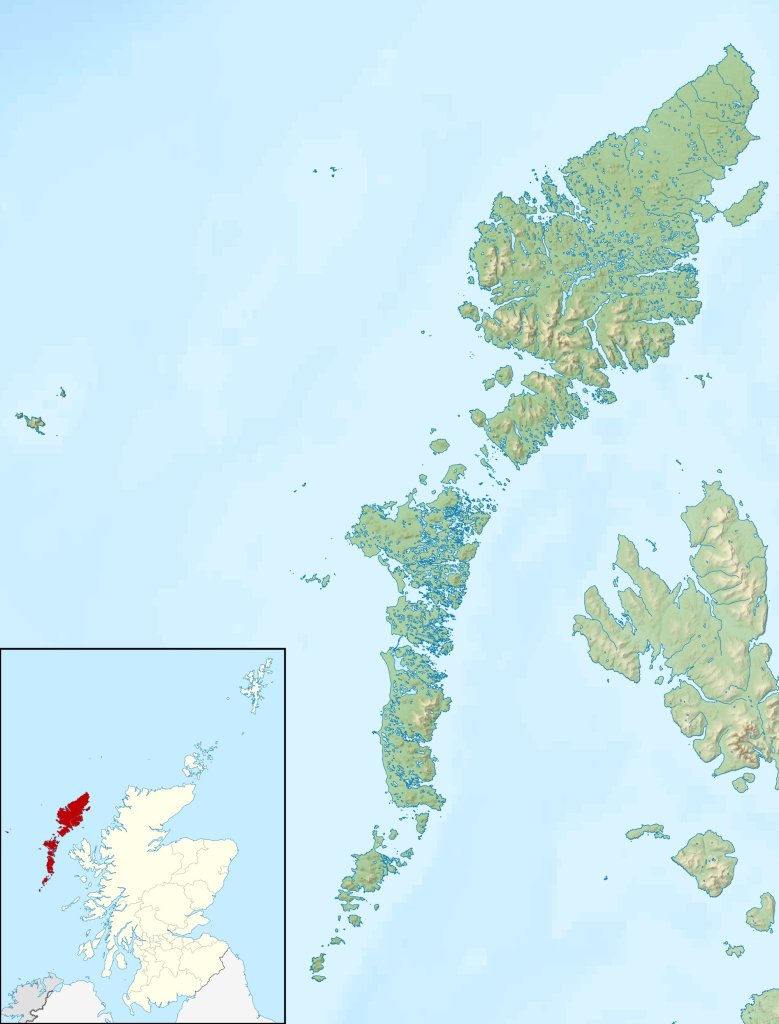

St Kilda is an isolated archipelago situated about 40 miles west of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. The three main islands, of which the largest is Hirta, are the remains of an ancient volcano which blew its top about 55 million years ago. The other main islands are Soay and Boreray.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

The small brown Soay sheep on these islands are descended from some of the earliest domestic sheep, which spread through Europe in the Bronze Age “reaching Britain’s remotest islands between three and four thousand years ago.” (Clutton-Brock and Pemberton, 2004).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

I have been lucky enough to visit St. Kilda twice – once last year (May 2022) and again this year (June 2023). Although, the story of the history and people of St. Kilda is incredibly fascinating – people have lived on St. Kilda for more than 4000 years – it was the sheep which captured my imagination most, during my two short visits. You only get a few hours ashore on this protected site owned by The National Trust for Scotland.

Soay, off the north-west corner of Hirta, supports the original population of Soay sheep, which was the source of the 107 animals introduced to Hirta in 1932. Prior to the islanders departing in 1930, there was an estimated population of between 1500 and 2000 animals, which belonged to the Lordship of the Isles, the MacLeods of Dunvegan, lairds from 1498 until 1930.

The Soay sheep population on St. Kilda have provided biologists with a good opportunity to study population regulation and natural selection in a relatively wild group of mammals. The National Trust Scotland describes the sheep as bring “feral”, i.e. living in the wild but descended from domesticated animals.

According to lead researchers, Tim Clutton-Brock and J. M. Pemberton, it has only been possible to measure the effects of population density and climatic variation on key factors – such as average survival, breeding success and recruitment – in a small number of studies of other vertebrates, mostly birds and deer. So this population of unmanaged, feral, Soay sheep is of particular interest to scientists.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Soay sheep are small: adult females (>5 yrs) typically only weigh about 24 kg (in August), whereas adult males average around 38 kg. They vary widely in colour, ranging from pale buff to very dark brown, and about 6% are uniformly dark, or ‘self-coloured’. Almost black. Soay sheep shed their fleeces each year between the end of April and early June (see below) and then regrowth occurs between June and August. Almost all of them were shedding their fleeces when I visited in May this year (2023).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

There are two types of males (a polymorphism): around 85% grow spiral horns (see below) while 15% have small, deformed horns (scurred).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

‘Boom-bust’ population dynamics

The number of sheep on St Kilda varies markedly: for example, fluctuating between a low of around 600 in 1960, to a high of about 2,000 in the late 1990’s. The population is described as being ‘unstable’, in biological parlance, meaning that many of the sheep starve to death in the winter as a result of a lack of resources. Nematode gut parasites also contribute to the mortality of malnourished sheep, the effects of the worms being exacerbated by food shortages.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Most of the Soay sheep living in and around the Village Bay area of Hirta have been marked with colour-coded ear tags (see below) and the location, activity, and plant communities on which they occur on, is regularly logged.

The first lambs are born in late March or early April, and are caught, tagged and weighed. A large proportion (e.g. 50% or about 240 animals) of the sheep in the Village Bay area are caught, re-weighed, and re-tagged if necessary, each year, and also checked for reproductive status and milk yield.

There has been a long-term trend for the sheep population size to increase, but for the sheep themselves to get smaller, an effect probably caused by climate change (see below).

Dark sheep are bigger

In Soay sheep, a dark coat colour is often associated with large size, a feature which which is heritable – meaning that it passed down from parent to offspring – and is usually positively correlated with fitness. However, researchers have found that the frequency of dark sheep has decreased in recent years. Why? It seems that other genes carried by the dark coated sheep have negative effects on their health – such as reduced reproductive success – that outweigh the benefits of being larger. So, although dark sheep are large, they have reduced fitness relative to their lighter coloured sheep. [N.B. it is the homozygous dark sheep that have a reduced fitness.]

There is however, another theory, namely that the warming climate may be responsible for the decline in frequency of dark Soay sheep on St Kilda.

“In the past, only the big, healthy sheep and large lambs that had piled on weight in their first summer could survive the harsh winters on Hirta. But now, due to climate change, grass for food is available for more months of the year, and survival conditions are not so challenging – even the slower growing sheep have a chance of making it, and this means smaller individuals are becoming increasingly prevalent in the population.” (Professor T. Coulson)

Recently, there has been petition, organised by some retired vets, asking the Scottish Government to reconsider the welfare of St Kilda’s sheep. The question is, I suppose, whether it is right to leave the Soay sheep to their own devices, i.e. living wild and unmanaged on St. Kilda, when hundreds of them die of starvation and parasitism every year. Studying them in an unmanaged state provides a lot of interesting information that can be applied elsewhere, but are they really wild? And if not, do we have a duty of care towards them?

The debate will undoubtedly go on, but the sheep population will no doubt continue to live and survive on these isles as they have done for thousands of years, whatever the outcome.

Links

https://soaysheep.bio.ed.ac.uk/

St. Kilda, Soay Sheep and Farming the Medieval Way

Scientists shear shrinking Soay sheep story

https://www.nature.com/articles/500387a

Black sheep really are bad

Feral on an uninhabited island, some dying from starvation: Uist campaigners bring St Kilda sheep concerns to Parliament

Life on the edge: celebrating a successful long-term ecological study

References

Clutton-Brock, T. M. and J. M. Pemberton (2004). Soay Sheep Dynamics and Selection in an Island Population. Cambridge University Press.

Clutton-Brock, T. H., Grenfell, B. T., Coulson, T., MacColl, A. D. C., Illius, A. W., Forchhammer, M. C., … & Albon, S. D. (2004). Population dynamics in Soay sheep. Soay sheep: dynamics and selection in an island population, 52-88.

Coulson, T., Catchpole, E. A., Albon, S. D., Morgan, B. J., Pemberton, J. M., Clutton-Brock, T. H., … & Grenfell, B. T. (2001). Age, sex, density, winter weather, and population crashes in Soay sheep. Science, 292(5521), 1528-1531.

Crawley, M. J., Pakeman, R. J., Albon, S. D., Pilkington, J. G., Stevenson, I. R., Morrissey, M. B., … & Pemberton, J. M. (2021). The dynamics of vegetation grazed by a food‐limited population of Soay sheep on St Kilda. Journal of ecology, 109(12), 3988-4006.

Gratten, J., Wilson, A. J., McRae, A. F., Beraldi, D., Visscher, P. M., Pemberton, J. M., & Slate, J. (2008). A localized negative genetic correlation constrains microevolution of coat color in wild sheep. Science, 319(5861), 318-320.

Gulland, F. M. D. (1992). The role of nematode parasites in Soay sheep (Ovis aries L.) mortality during a population crash. Parasitology, 105(3), 493-503.

Ozgul, A., Tuljapurkar, S., Benton, T. G., Pemberton, J. M., Clutton-Brock, T. H., & Coulson, T. (2009). The dynamics of phenotypic change and the shrinking sheep of St. Kilda. Science, 325(5939), 464-467.

Preston, B. T., Stevenson, I. R., Pemberton, J. M., & Wilson, K. (2001). Dominant rams lose out by sperm depletion. Nature, 409(6821), 681-682.

Preston, B. T., Stevenson, I. R., Pemberton, J. M., Coltman, D. W., & Wilson, K. (2005). Male mate choice influences female promiscuity in Soay sheep. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272(1561), 365-373.