Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

There is an old saying about bees that their wings are too small for their bodies. However, this misconception about bee flight being ‘impossible’ can be traced back to erroneous speculations made in the 1930s by a French entomologist called August Magnom, and has long since been debunked. The myth has endured, however, perhaps because we like to think that some things in nature are outwith, or beyond, the understanding of science and the rules of physics? In reality, a huge amount is now known about the science of bee flight.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Nevertheless, there is also some traction in the idea that bees shouldn’t be able to fly because ‘conventional fixed-wing aerodynamic theory is indeed insufficient to explain the flapping flight of bees and other small insects’ (Altshuler et al., 2005).

However, we now know that the particular rapid low-amplitude wing motion of bees during flight is sufficient to maintain their weight and they can easily generate excess aerodynamic power by raising the stroke amplitude while a maintaining constant frequency wingbeat. Described in detail in a paper by Altshuler et al. (2005).

Honeybees and bumblebees hover using a shallow stroke amplitude and high wingbeat frequency, and this lower-efficiency stroke means that they have excess power available for other things, such as carrying loads of pollen and nectar.

The secret of honeybee flight has been described as follows:

“the unconventional combination of short, choppy wing strokes, a rapid rotation of the wing as it flops over and reverses direction, and a very fast wing-beat frequency” (see here and Altshuler et al., 2005).

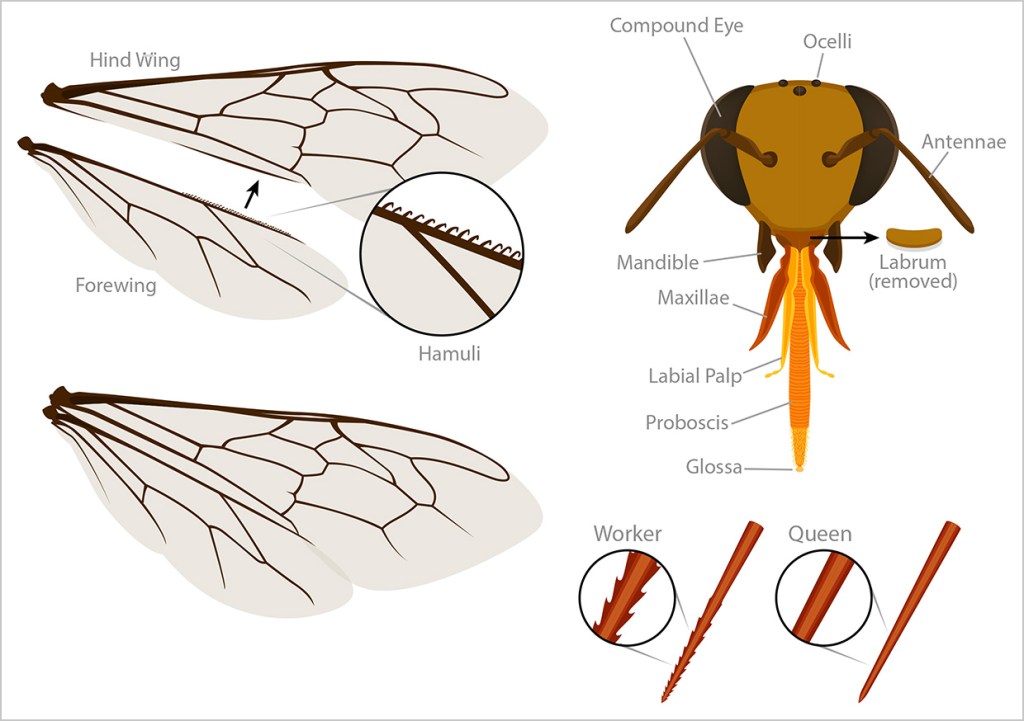

Fastening the wings together

Bees use a row of tiny hooks – called humuli – to attach their front and hind wings together during flight, enabling both wings to move as a single, flexible aerofoil. These hook-like setae are located on the leading edge of the hindwings of most hymenopterans and interlock with a thickened and recurved margin on the trailing edge of the forewing.

Insect wings bend and twist during flight

Bee wings are not rigid, indeed they are highly flexible membranes containing a special, rubber-like protein called resilin. This highly elastomeric substance enables the wings to twist and rotate during flight: short, quick sweeping motions from front and back. The flexibility of the wing is illustrated in these photographs of buff-tailed bumblebees (Bombus terrestris), below.

And, of course, bees can also fly backwards!

Wing beats

The wings of honeybees beat over a short arc of about 90 degrees, but ridiculously fast, at around 230 beats per second, for example, when in hovering flight. When ascending in air, bees increase their wing stroke amplitude by 30%–45%, which of course produces a much higher wing tip velocity relative to hovering.

Bumblebees with larger wings, like this buff-tailed bumblebee (below) tend to have lower wingbeat frequencies.

The wingbeat frequency of the Asiatic honeybee, Apis cerana (below) is higher than that of the western honeybee, Apis mellifera, at 306 Hz and 235 Hz, respectively, for worker bees.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

The larger the insect and its wings, like this large black Bombus eximius from northern Thailand (below), the lower the wingbeat frequency, as it takes longer for the larger wings to complete a wing beat (see Parmezan, et al., 2021).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

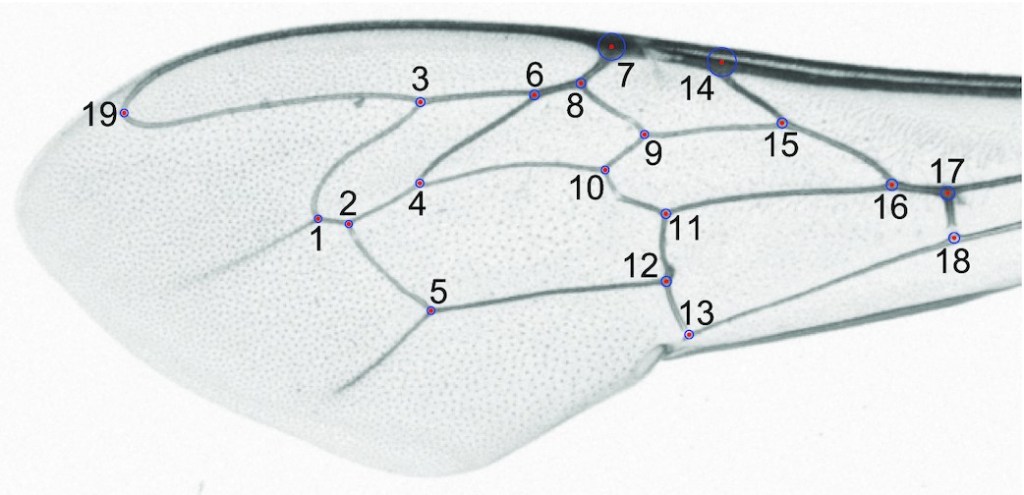

Variation

There is quite a large geographic variation in honeybee wing shape in Europe, probably as the result of natural selection. So-called, ‘landmarks’ – at wing vein intersection points – on a honey bee wing can be used to identify the geographic origin of an individual (below).

Wear and tear

The condition of the wings – or ‘wing wear‘ – is sometimes used to age bees, but it is a rather crude index. There is however, a fairly good correlation between wing wear and age in some species, where it has been studied, such as the wool-carder bee, Anthidium manicatum (below).

By Didier Descouens – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15744584

Although insect wings slowly degenerate with use, individuals do not necessarily accumulate wear at the same rate, and the damage appears to come from the flight behaviour of the bee – especially how many collisions it accumulates – rather than time spent flying. In other words, wing usage and flying ability rather than hours flying!

Weather conditions also play a role. In windy weather, bumblebees can still fly, but they have to beat their wings faster and increase the amplitude of their wing strokes to compensate for the turbulent conditions. This turbulence-mitigation strategy enables bees to keep on foraging, but they increase the energetic costs of flying and perhaps subject the wings to greater wear.

In a study of Canadian bumblebees, Bombus spp., Danusha Foster and Ralph Cartar of the University of Calgary, found that the frequency of collisions which occur whilst bees are out foraging, are uniquely associated with the loss of wing area. They found that wings collide with vegetation relatively often – roughly once every second in some cases! – particularly when the bees are manoeuvring within vegetation. Collisions also occur when a bee hits its wings on the inflorescence or flower on which it is foraging, during take-off and landing (below).

Wing wear increases the chance of mortality in bumblebees, probably by increasing the likelihood of predation. Perhaps a bit of wing damage takes the edge off their flying ability and makes it just a bit more likely that they will fall prey to a bird, like a fly-catcher or a shrike?

Increased wing damage effectively increases the wingbeat frequency, because when a wing is smaller, it needs to beat faster to generate more lift.

Clipping the wing tips of bumblebees – e.g. removing approximately 22% of the area of both forewings – reduces their manoeuvrability and significantly reduces the maximum acceleration of the bees in flight. Clipping only one wing tip has less effect however, suggesting a capacity to cope with a certain amount of injury.

I captured a photo of one such lopsided wing injury in a large bumblebee I came across in Galicia, Spain. The left fore-wing on this large bumblebee (below, left) seemed little more than an oar, yet it was oscillated back and forth at high speed, and the insect did not appear to be inconvenienced in any way!

Experiments have demonstrated that the flight behaviour of bumblebees is highly resilient to major changes in wing area and asymmetry. The flight behaviour of bumblebees with with 40% of their total wing area clipped, was not very different from other individuals with fully intact wings. This suggests to me that evolution has, over time (hundreds of millions of years in the case of insect wings!), selected for wings that are remarkable resilient and adaptable to damage.

Wing damage also has deleterious effects on the survivorship and foraging behaviour of honeybees. Studies on honeybees in the UK by Andrew Higginson et al. (2011) suggested that wing damage causes a reduction in foraging ability, and that damaged bees have to adjust their foraging behaviour accordingly. The wing-damaged bees carried out shorter and/or less frequent foraging trips and foraged closer to the hive. Clearly, they knew their own limitations and made the necessary adjustments!

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Links

https://askabiologist.asu.edu/how-do-bees-fly

References

Altshuler, D. L., Dickson, W. B., Vance, J. T., Roberts, S. P., & Dickinson, M. H. (2005). Short-amplitude high-frequency wing strokes determine the aerodynamics of honeybee flight. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(50), 18213-18218.

Basibuyuk, H. H., & Quicke, D. L. J. (1997). Hamuli in the Hymenoptera (Insecta) and their phylogenetic implications. Journal of Natural History, 31(10), 1563-1585.

Crall, J. D., Chang, J. J., Oppenheimer, R. L., & Combes, S. A. (2017). Foraging in an unsteady world: bumblebee flight performance in field-realistic turbulence. Interface focus, 7(1), 20160086.

Foster, D. J., & Cartar, R. V. (2011). What causes wing wear in foraging bumble bees?. Journal of Experimental Biology, 214(11), 1896-1901.

Haas, C. A., & Cartar, R. V. (2008). Robust flight performance of bumble bees with artificially induced wing wear. Canadian journal of zoology, 86(7), 668-675.

Higginson, A. D., Barnard, C. J., Tofilski, A., Medina, L., & Ratnieks, F. (2011). Experimental wing damage affects foraging effort and foraging distance in honeybees Apis mellifera. Psyche: A Journal of Entomology, 2011.

Jernigan, C. M.. (2017, October 24). How Do Bees Fly?. ASU – Ask A Biologist. Retrieved October 20, 2023 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/how-do-bees-fly

Łopuch, S., & Tofilski, A. (2019). Use of high-speed video recording to detect wing beating produced by honey bees. Insectes Sociaux, 66, 235-244.

McMasters, J. H. (1989). The Flight of the Bumblebee and Related Myths of Entomological Engineering: Bees help bridge the gap between science and engineering. American Scientist, 77(2), 164-169.

Magnan, A. (1934). Locomotion in Animals: Vol. 1: The flight of insects . Hermann & Cie, Paris Publishers.

Michels, J., Appel, E., & Gorb, S. N. (2021). Coupling wings with movable hooks–resilin in the wing-interlocking structures of honeybees. Arthropod structure & development, 60, 101008.

Mountcastle, A. M., Alexander, T. M., Switzer, C. M., & Combes, S. A. (2016). Wing wear reduces bumblebee flight performance in a dynamic obstacle course. Biology letters, 12(6), 20160294.

Mueller, U. G., & Wolf-Mueller, B. (1993). A method for estimating the age of bees: age-dependent wing wear and coloration in the wool-carder bee Anthidium manicatum (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Journal of Insect Behavior, 6, 529-537.

Oleksa, A., Căuia, E., Siceanu, A., Puškadija, Z., Kovačić, M., Pinto, M. A., … & Tofilski, A. (2023). Honey bee (Apis mellifera) wing images: a tool for identification and conservation. GigaScience, 12, giad019.

Parmezan, A. R., Souza, V. M., Žliobaitė, I., & Batista, G. E. (2021). Changes in the wing-beat frequency of bees and wasps depending on environmental conditions: a study with optical sensors. Apidologie, 52(4), 731-748.

Wonderful post – and thanks for debunking that old myth – one I’ve heard repeated so many times, I took it as gospel myself (oops)! Great photos document this very interesting article. I didn’t know about the little “teeth” that join the forewing and hindwing together, thanks also for highlighting that info for us. If I’m not mistaken, that’s a similar technique to how bird feathers, made of individual tiny strands, form a single plane.

Fascinating. Thank you for this very ambitious post.