Millipedes (class Diplopoda) may not be everyone’s ‘cup of tea’, but they do have fascinating love lives! Some giants from Madagascar even ‘sing’ to each other; a form of stridulation that males use to try and persuade females to uncoil and mate with them!

In most, if not all animals, from humans to millipedes, the interests of the two sexes are not always exactly the same. We might say that males and females have different approaches to sex! These differences arise as a result of their slightly different genomes, plus the fact that each sex does not necessarily make equal contributions to the production of offspring. For example, females produce a much bigger, more costly gamete (egg) than males, so they are usually more discerning in their choice of a mate. Males can usually produce thousands, if not millions of ‘cheap’ sperms, so they are usually happy to mate more often. It’s not always this way round, but females are generally the more choosier sex.

As well as making unequal material contributions, one sex – not always the female (see below) – also spends more time looking after the offspring. This all leads to what biologists call sexual conflict, and these mating tussles have, over evolutionary time, produced some remarkable innovations and adaptations.

Because they have somewhat different interests, at least in evolutionary terms, either sex can evolve ways and means of trying to force their own way, or contrarily, mechanisms for resisting such antagonistic behaviour. In millipedes, males sometimes attempt to force the female into the mating position, and mating can also involve a battle over how long to remain joined together in copulation. In some millipedes, the males appear to control the time spent in mating, but in others, it is the females who seem to be in control. It often comes down to who is larger, with females being bigger in some species.

However, despite these differences, males and females do need to mate if the species is going to survive, so sexual conflicts are perhaps better thought of as a mating ‘tug-of-wars’.

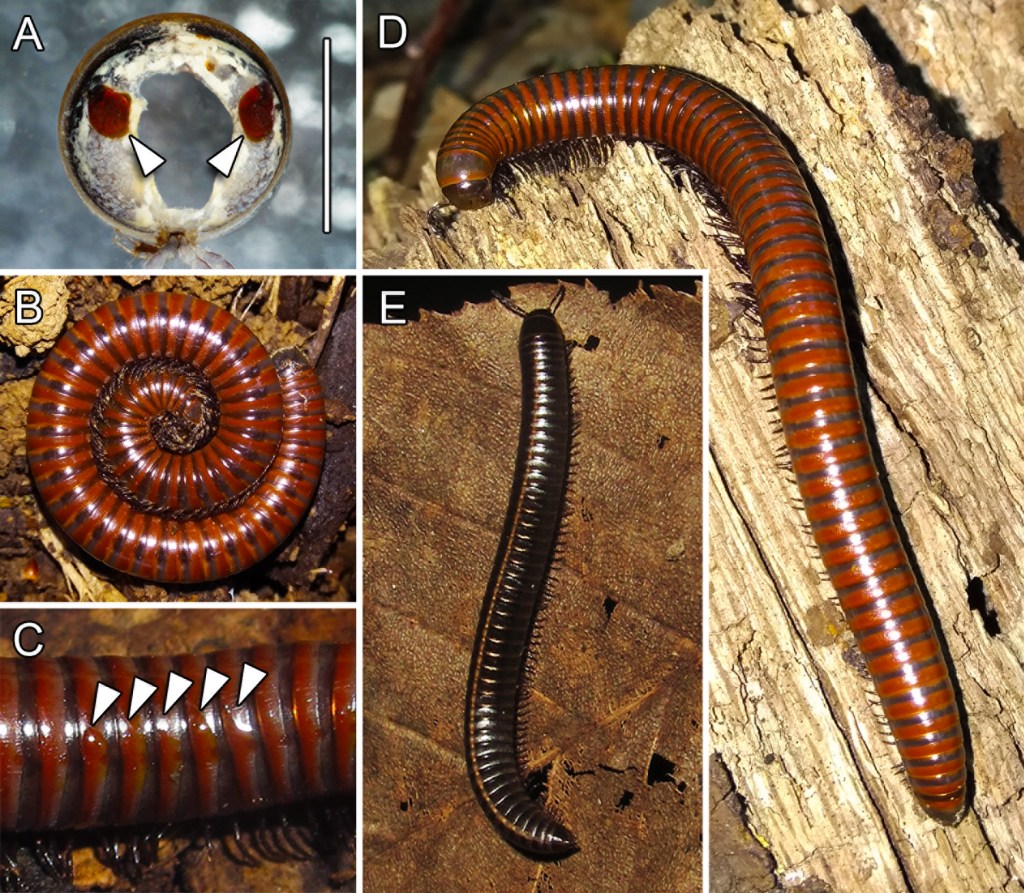

As we have seen, sexual struggles in millipedes tend to occur over the duration of copulations. In some species, such as the large red millipede Centrobolus inscriptus, the males control the duration of copulation and they continue to maintain genital contact with females when there are other competitor males around, i.e. mate guarding.

Some of these large red millipedes from southern Africa are kept as pets! See here. Their red colour is probably a warning to any would-be predator that they are poisonous: i.e. aposematic coloration. Surprisingly, perhaps, millipedes are attacked by a wide range of other invertebrates – including ants, beetles, predaceous bugs, spiders, and slugs – as well as birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians. However, they have a have a broad range of chemical and mechanical defences, including the ability in some species, roll themselves up into spheres or flattened discs, with the head, antennae and legs entirely enclosed; an adaptation called enrollment, or vollvation.

By Chiswick Chap – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0,

Courtship is the process by which individuals of the opposite sex come together to determine whether they are ready to mate and whether they wish to choose that particular individual as a partner. It may come as a surprise to some people, that mating in insects and other arthropods is usually consensual. They make decisions and choices about a partner, and courtship behaviour – which is sometimes rather stereotyped – provides a way to both stimulate and evaluate one another. The outcome, being acceptance or rejection.

Courtship in millipedes seems to be mainly an affair in which the male tries to persuade the female to uncoil herself and allow mating to occur! However, it can involve the male, walking along the female’s back and stimulating her with rhythmic movements of his legs. The mounting stage usually involves

the male running up the back of the female and clinging to her using tarsal pads on the legs.

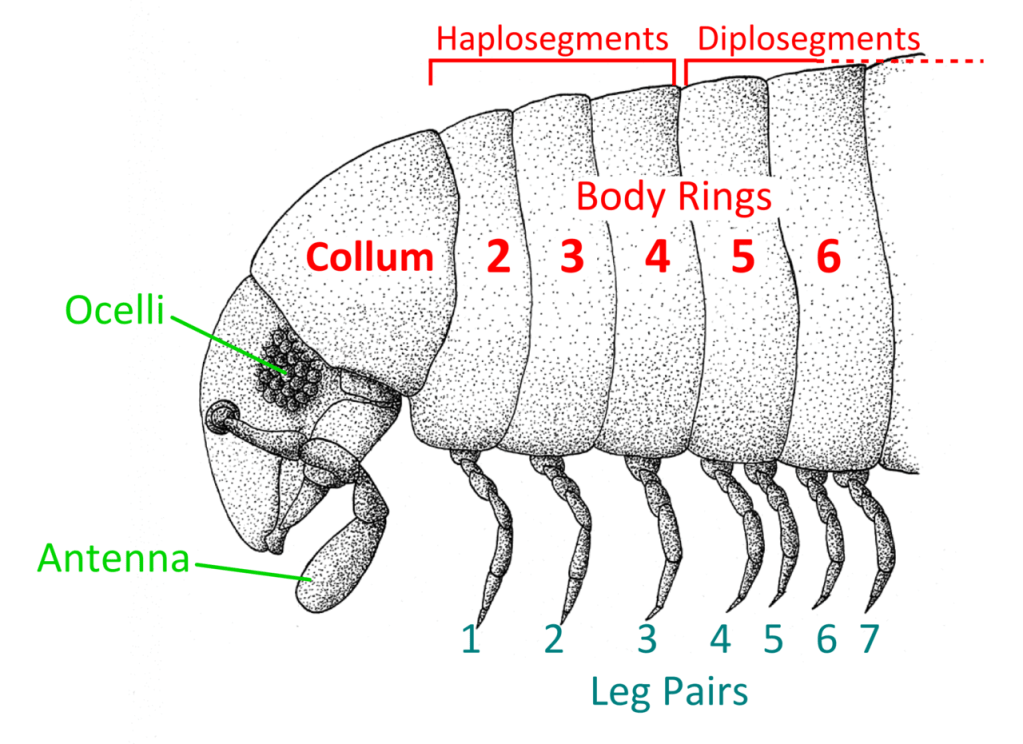

It all happens in the first seven segments!

In julid millipides (Superorder:Juliformia), the male typically makes contact head-on, then commences to forcefully wrap itself around the female. The male’s head is located slightly above the female’s during mating, thereby lining up his gonopods – which located on the seventh body ring – with the female’s vulvae, which occur in the second body ring (see below).

Mating millipedes, Trigoniulus corallinus, male below.

By Mark Yokoyama Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED

“In most millipedes… the male’s testes are located in the body, starting behind his second pair of legs. But his gonopods, the specialized pair of legs used to insert sperm into the female, are way back on his legs of the seventh body ring.” (Link 2.)

In the European millipede Pachyiulus hungaricus (Julidae) (below), ‘if the female is receptive and ready to mate, it will uncoil the anterior part of its body and expose the gonopores. The male then ejects its gonopods, and the next step in achieving copulation is extrusion of the female’s vulvae’ (Jovanovic et al., 2017).

During copulation, millipedes are often found in a parallel position (below) or with the male coiled around the female, sometimes forming a ‘sexual collar’, with hydraulic movements in the region of genital contact.

According to Brandt et al. (2022), in the millipede Spinotarsus glabrus, the male continually taps on the female’s head with his antennae, a fairly common feature of courtship. The female initially tries to escape, bending its body for about a minute, then remaining motionless for the rest of the copulation.

Mate guarding

The male may be happy to stand guard over the female once he has mated, to prevent other males from mating with her, but the female usually wants to get on with feeding and egg laying and in some species is able to terminate the union when she wants.

By budak Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED.

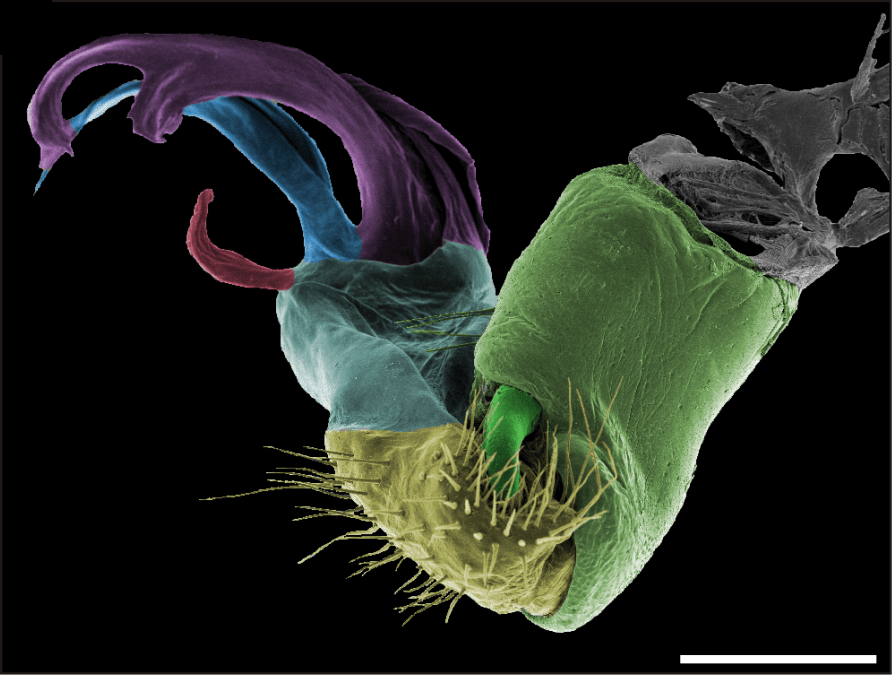

Sexual conflicts between the sexes in millipedes have driven the evolution of structures that appear to aid them in forcing and resisting copulation. For example, males of some species possess tarsal pads for grasping females as well as genital processes for holding the female. Females, on the other hand, as described above, can coil up to avoid mating – a tactic for choosing the right mate? – and some have spines on their bursa copulatrix (a bag shaped organ used to keep sperm) to exclude males from their stores of sperm from previous matings. Males can use specialised devices (below) to remove the sperm of rivals – sperm competition.

Drago, L., Fusco, G., Garollo, E., & Minelli, A., CC BY 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Rejection is a tightly coiled female!

The precopulatory coiling by the female is very similar to the behaviour they adopt when trying to avoid being eaten by a predator. It is, in effect, a test of the male’s quality because fitter males are better able to uncoil females. In other words, females will uncoil for males they find attractive and wish to mate with and allow access to their gonopores. Rejection is, therefore, a tightly coiled female!

Photo by Muhammad Mahdi Karim GFDL 1.2

Males are also not above forming a threesome when competition is fierce: males can form triplet associations with copulating pairs in the tropical millipede Alloporus uncinatus. Both sexes can mate multiple times.

Chirping giants!

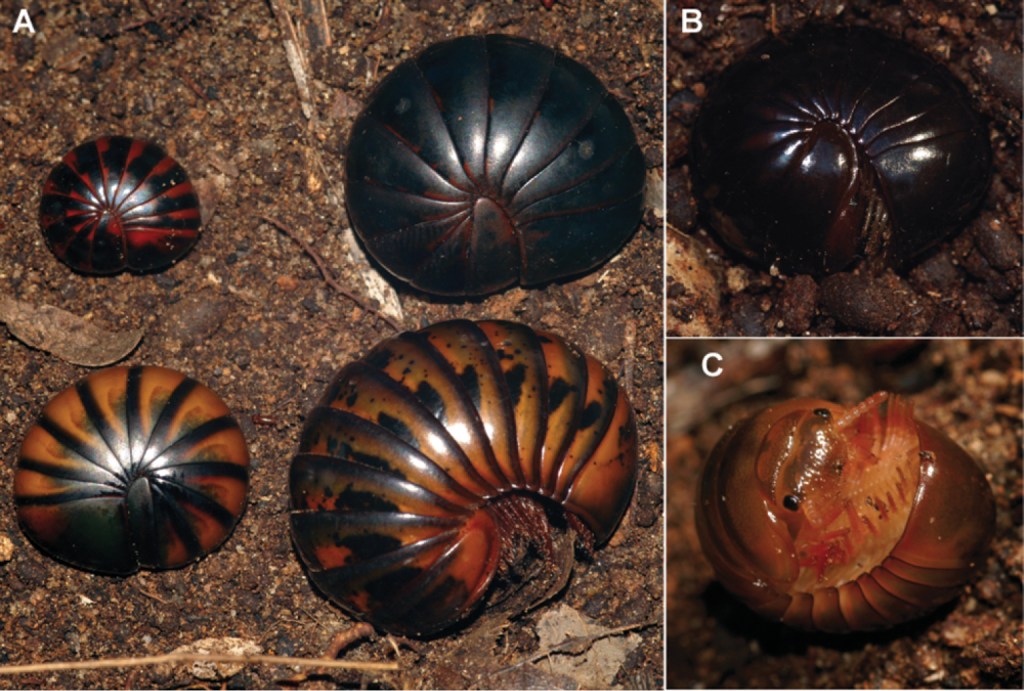

Giant pill-millipedes (Diplopoda: Sphaerotheriida) have stridulatory organs (in both sexes), which play an important role in mating although this fascinating behaviour does not seem to have been studied in the field, as far as I can tell. The anatomy of the stridulatory organs is well-documented for taxonomic purposes, but how these organs are used under natural conditions is less well known.

The genus Sphaerotherium comprises at least 60 species of large pill millipedes, including tropical and subtropical species. Individuals of both sexes roll into a spherical ball, which is part of the mating system. However, Sphaerotherium males usually stridulate only when in contact with a female: either to prevent them from volvating into a ball or to stimulate them to uncoil when already rolled up.

In millipedes in the genus Sphaerotherium, males usually stridulate only when they are attempting to initiate mating. Successful uncoiling of the larger female requires a specific frequency of vibration to facilitate mating, and females will not respond to an undesirable frequency, remaining curled up in the conglobated position.

Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED

Female giant pill-millipedes usually roll up – a defensive behaviour – when touched by a male. Some giant pill millipede species from Madagascar are as large as an orange when rolled up.

Stridulation is a relatively rare phenomenon in millipedes, only known from about 158 out of the 15,000 descrived species. The sound produced by one nodule-like structure (plectrum) being moved against a ridged surface (pars stridens) or vice versa. These stridulation organs have been called a male ‘harp’ and a female ‘washboard’, the latter being located at the caudal end of the female.

Giant pill millipedes (below) have 13 body segments and 21 pairs of walking legs and can roll up into a tight spherical shape, a process called conglobation.

Millipedes are hugely valuable members of a diverse range of ecosystems, functioning as detritivores, eating decaying vegetation, and recycling plant material. They are harmless to humans and deserve our respect and protection as some of the oldest land animals. Some of the giant species have highly localised distributions and are threatened by habitat loss and other anthropogenic activities such as mining.

Links

1. Global taxonomic database of all described millipede, pauropod, and symphylan species: https://www.millibase.org/index.php

2. How Millipedes Actually “Do It”: Matinghttps://scitechdaily.com/how-millipedes-actually-do-it-scientists-finally-figure-out-mystery-of-millipede-mating/

3. https://alloporus.blog/2017/08/11/sex-in-millipedes/

“We are talking, multiple partners, rape, the occasional homosexual mistake, sperm competition, mate guarding, and elaborate genitalia.“

4. Singing millipedes. https://www.wired.com/2011/10/millipede-stridulation/

5. https://images.app.goo.gl/HXJyiq5aV3NRBrx48https://images.app.goo.gl/HXJyiq5aV3NRBrx48

6. https://youtu.be/O_Q1gYi9Nig?si=JbH_8IV7ZYpxmKeOhttps://youtu.be/O_Q1gYi9Nig?si=JbH_8IV7ZYpxmKeO

7. Pill Millipede facts. https://youtu.be/O_Q1gYi9Nig?si=Y0WnvzY1ZcdF0Zid

8. Titanium vs. Millipedes: new species discovered in Madagascar threatened by mining. https://news.mongabay.com/2014/08/titanium-vs-millipedes-new-species-discovered-in-madagascar-threatened-by-mining/

References

Ambarish CN, Sridhar KR. Zoogeography and Diversity of Endemic Pill-Millipedes in the Southern Hemisphere (Sphaerotheriida: Diplopoda). Discovery, 2022, 58(317), 385-398

Brandt, J., Reip, H. S., & Naumann, B. (2022). In flagranti-Functional morphology of copulatory organs of odontopygid millipedes (Diplopoda: Juliformia: Spirostreptida). bioRxiv, 2022-11.

Chapman, T., Arnqvist, G., Bangham, J., & Rowe, L. (2003). Sexual conflict. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 18(1), 41-47.

Cooper, M. I. (2017). Copulation and sexual size dimorphism in worm-like millipedes. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies, 5(3), 1264-1266.

Cooper, M. I., & Telford, S. R. (2000). Copulatory sequences and sexual struggles in millipedes. Journal of Insect Behavior, 13, 217-230.

Ilić, B., Unković, N., Knežević, A., Savković, Ž., Ljaljević Grbić, M., Vukojević, J., … & Lučić, L. (2019). Multifaceted activity of millipede secretions: Antioxidant, antineurodegenerative, and anti-Fusarium effects of the defensive secretions of Pachyiulus hungaricus (Karsch, 1881) and Megaphyllum unilineatum (CL Koch, 1838)(Diplopoda: Julida). Plos one, 14(1), e0209999.

Jovanovic, Z., Pavkovic-Lucic, S., Ilic, B., Vujic, V., Dudic, B., Makarov, S., … & Tomic, V. (2017). Mating behaviour and its relationship with morphological features in the millipede Pachyiulus hungaricus (Karsch, 1881)(Myriapoda, Diplopoda, Julida). Turkish Journal of Zoology, 41(6), 1010-1023.

Shear, W. A. (2015). The chemical defenses of millipedes (Diplopoda): biochemistry, physiology and ecology. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 61, 78-117.

Telford, S. R., & Dangerfield, J. M. (1993). Mating tactics in the tropical millipede Alloporus uncinatus (Diplopoda: Spirostreptidae). Behaviour, 124(1-2), 45-56.

Telford, S. R., & Dangerfield, J. M. (1994). Males control the duration of copulation in the tropical millipede Alloporus uncinatus (Diplopoda: Julida). African Zoology, 29(4), 266-268.

Wesener, T., Köhler, J., Fuchs, S., & van den Spiegel, D. (2011). How to uncoil your partner—“mating songs” in giant pill-millipedes (Diplopoda: Sphaerotheriida). Naturwissenschaften, 98, 967-975.

Wesener, T., Le, D. M. T., & Loria, S. F. (2014). Integrative revision of the giant pill-millipede genus Sphaeromimus from Madagascar, with the description of seven new species (Diplopoda, Sphaerotheriida, Arthrosphaeridae). ZooKeys, (414), 67.

Dear Ray,

You have done a lot of commendable works here for the millipede, towards which I have always had a fascination. The pill millipede seems to be the “cutest” of them all. Thank you very much for sharing with us a thoroughly enjoyable overview of the sexual conflict and sex life of millipedes.

Academic interest and fascination aside, it seems that we both find great beauty in insects. Yet, beauty is not entirely subjective and is not just in the eye of the beholder. There is strong, unshakable evolutionary basis for our sense, feeling, perception and conception of beauty. In addition, there are evolutionary bases in people’s sense of morality and in their behaviours. You will find a great deal of new understandings in multidisciplinary fields such as sociobiology, evolutionary psychology and behavioural sciences, epigenetics, brain and cognitive sciences, gene-culture coevolution, biophilia and many more. . . . .

Indeed, the late Edward O Wilson, an entomologist specializing in myrmecology, had proposed the idea of biophilia to explain and encapsulate such matters. You may have already known that Wilson’s seminal book “The Diversity of Life” has given us the terms “biodiversity” and “biophilia”. I have owned a copy of the book for 20 odd years. That we can learn a great deal about ourselves and Nature via the notion of “Biophilia” as first proposed by Edward O Wilson is in some ways both refreshing and revolutionary.

One of my most favourite books of Edward O Wilson is none other than “Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge”, which is a national bestseller, not to mention that Wilson has received many fellowships, awards and honours, including two Pulitzer prizes. I love the word “Consilience”, which I have used in my very long “About” page.

My special and academically written post entitled “We have Paleolithic Emotions; Medieval Institutions; and God-like Technology” is a detailed and expansive tribute to Wilson. The post has been much improved and expanded. The direct link is:

Dr Craig Eisemann, also a retired entomologist like you, has also contributed to the said post, which contains a complete list of Wilson’s works and awards as well as other achievements and associations.

Given the complexity and intricate formats of the post, it is best viewed on the large screen of a desktop computer.

I welcome your input there since I am curious to know what you make of my said post as well as your perspectives on those matters discussed in my post.

Yours sincerely,

SoundEagle

Fascinating post Ray, thank you. I love seeing millipedes and love the pics but know so little about them. Until now. 🙂

Fascinating, Ray, absolutely fascinating. Thank you for expanding my rather rudimentary knowledge of millipedes. 😲