“Aphids, despite their apparently limited behavioural repertoire, are in fact masters (or perhaps more accurately, mistresses) of adaptation and evolutionary flexibility” (Loxdale et al., 2020).

In this blog, I look back at what was a bumper year for one particular aphid (the rose-grain aphid), the summer of 1979, and the species just happened to be the one I was studying for my PhD! Finally, I take a quick look at the cosy, mutually beneficial relationship between ants and aphids.

Aphids – members of the superfamily Aphidoidea – might not be everyone’s cup of tea, but they are insects with a fascinating range of biological adaptations that have enabled them to thrive in agroecosystems devised by humans. For their versatility and resilience in a changing world, we call them pests! But really, they are just very good at multiplying up their populations on the summer hosts we have chosen as food crops. They are also pretty good at thriving on other species we have chosen to grow in our gardens! Of course, they are not really machines; they are an ancient group of sap-sucking bugs which have diversified onto a large number of trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants. Complex life-cycles and an ability to reproduce asexually, are keys to their success.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

I have a certain vested interest in aphids as they helped me to get my doctorate! I spent three consecutive summers on my hands and knees in a wheat field, counting, recording, and observing the reproduction and development of one particular species of cereal aphid, called the rose-grain aphid (below).

Photo by InfluentialPoints (CC BY 3.0)

The rose-grain aphid or rose-grass aphid, Metopolophium dirhodum (above), as their name suggests, is a heteroecious – i.e. host alternating – species, which spends the winter on one host plant (roses), then flies off to build up their numbers on another host (grasses), in the summer. Aphid life cycles are nicely explained here by Simon Leather.

In the spring, asexual female aphids called fundatrices hatch from winter eggs and begin reproducing parthenogenetically for several generations on their primary host (wild and cultivated plants of Rosa L. spp.). The oviposition site on which they were deposited depends on the species of rose. For example, on Rosa rugosa and R. canina, eggs are primarily laid beside, or onto, the prickly thorns (Vereshchagina & Gandrabur, 2021).

However, it worth pointing out that roses can support several other, different species of aphid in the spring and summer, the most common being Macrosiphum rosae (below).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

It should be clear from the photographs (above and below), that rose aphids come in different colours! Red and green in this case. Colour in aphids can either be determined genetically or it can be triggered environmentally (Williams & Dixon, 2007). In fact, it is not altogether clear why there are differently coloured forms, but they can have different reproduction rates, host preferences, feeding sites, temperature tolerances and susceptibility to natural enemies. So it may be a way of the aphids hedging their bets by generating variability in an unpredictable world!

Going back to the rose-grain aphid, the founding female (the fundatrix) establishes a sizeable clone of individuals during the spring before the emigrants migrate away from the rose tree or bush in early summer, finding their way onto the secondary host plants (members of the grass family Poaceae). On the secondary hosts, such as wheat and barley, parthenogenetic reproduction continues for many generations throughout the summer, producing summer populations of winged and wingless aphids (all females) which build up to huge numbers in certain years. In late summer, winged males and forms called gynoparae (females whose offspring develop into sexual forms) appear in aphid colonies and these fly back back to their primary hosts (wild roses). The gynoparae then give birth to sexual females, which mate with males and produce overwintering eggs (Gandrabur et al., 2023).

Parthenogenetic reproduction

“Aphids reproduce mainly asexually, one female producing 10-90 offspring in 7-10 days and therefore, theoretically, could produce billions of offspring in one growing season in the absence of mortality factors.” (Loxdale et al., 2020).

The winged forms of M. dirhodum that migrate to herbaceous plants such as wheat in the spring (called emigrants) produce, on average, about 63 ± 7 offspring by parthenogenesis over a two week period (Gandrabur, et al., 2023). The next generation of winged and wingless offspring (called exules) produce about 120 offspring in 14 days. So, numbers can rapidly increase (exponentially) over multiple generations, with the actual populations determined by the controlling effects of predators and parasites, together with the vagaries of the weather.

An aphid ‘plague year’ (1979)

The summer of 1979 – when I was doing my doctoral research – was an exceptional year for the rose-grain aphid. In fact, there has not been such an abundance of this species since then. At the time, there was a bit of a debate as to where the aphids had come from! Of course some press reports blamed our European neighbours! Undoubtedly, some of the winged alates may have developed first in the warmer climate of the south of France and then gradually spread northwards across Europe (Dewar et al.,1980). But the majority of the aphids developed here in the UK. By the end of July in 1979, the cereal fields of Britain were producing vast numbers of rose-grain aphids. The populations had increased exponentially as a result of favourable weather and an absence of controlling factors, i.e. predators and disease. Some scientists blamed the very cold winter of 1978/1979 – the coldest winter since 1962-63 – for wiping out the predators and parasites which normally keep aphid populations in check.

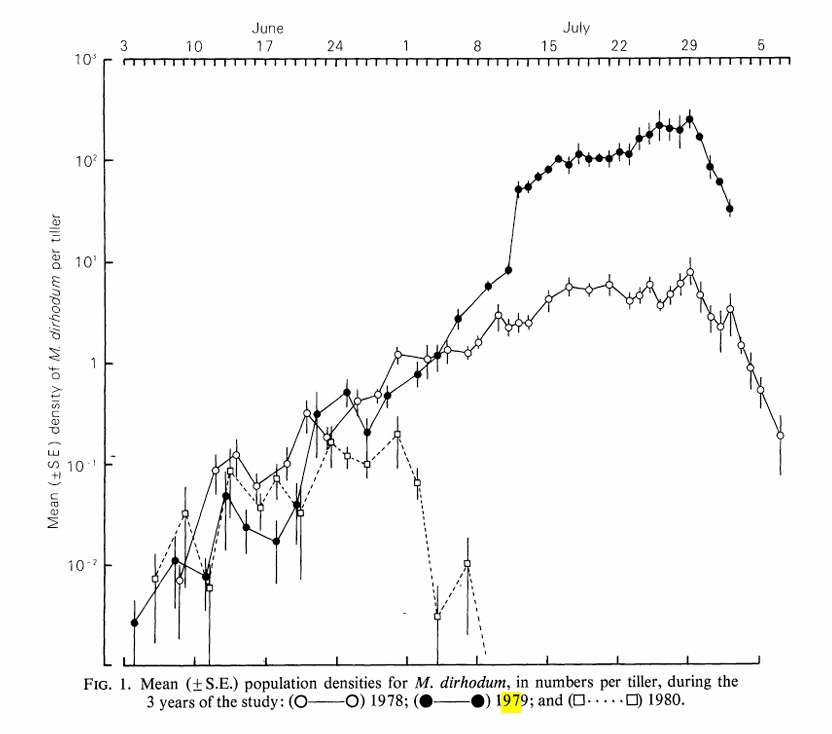

Anyway, in the field I was sitting in, counting aphids in Bedfordshire in 1979, numbers of rose-grain aphids reached a peak of 262 + 56 aphids per tiller of wheat (Cannon, 1986). Bear in mind that there can be up to 100-plus tillers (stems) per square foot, in old metrics, or about 500 tillers per square metre. That’s over a billion aphids per hectare! The plants were positively dripping with aphids and their honey dew! No wonder there were press reports of an ‘aphid plague’ (Heathcote, 1979).[ N.B. this followed the so-called ladybird plague of 1976!]

So there were billions, probably trillions, of rose-grain aphids flying over southern England by the end of July 1979. Tiny little winged aphids (see below), each weighing about 0.2mg or less, but collectively weighing more than a 1,000 tonnes! (Schaefer et al., 1979). In retrospect, this has to be a severe underestimate of the aerial biomass of aphids at the time, as there are over a million hectares, just of wheat, in England.

Photo by InfluentialPoints (CC BY 3.0)

I have to confess, I nearly went mad counting aphids in 1979, sitting in a wheat field for hours and hours every day, throughout June and July and into the beginning of August (below), but it was a great season in which to gather data. My Professor was disappointed that I had not followed the decline of the population down to the base line! But I was shot, completely exhausted and mentally spent from counting aphids non-stop for nearly three months! When I closed my eyes at night, all I could see was aphids crawling up wheat leaves! I needed a shot of whisky just to get to sleep. Enough was enough; I escaped for a well-deserved holiday in Greece: wondering whether I was going to do it all again the next year! Of course I did, and luckily for me, the population was very low in the last year of my PhD. I had three contrasting years to analyse as shown in the following graph (Cannon, 1986). See below.

Cut to the present!

The first DNA sequencing was performed in 1977, about the time I started my doctoral studies, by the great Frederick Sanger at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge. He won the Nobel Prize twice! However, the process was not automated until the late 1980s and it was not until 1996, that things really got going, with the introduction of a new DNA sequencing technique called pyrosequencing (see A History of Sequencing by Keegan Schroeder).

The first insect genome assembly (for Drosophila melanogaster) was published in the year 2000 (Adams et al., 2000). N.B. the fruit fly genome encodes ∼13,600 genes. Today, nuclear genome assemblies have been elucidated for more than a thousand insect species, and the number is growing rapidly.

In 2022, a team of Chinese scientists published the first high-quality chromosome-level genome for Metopolophium dirhodium, showing that it encoded 18,003 protein-coding genes (Hurray! More than the fruit fly!). They also identified a number of genes that are related to wing dimorphism in this species (Zhu et al., 2022; 2024).

Photo by Line Sabroe Flickr CC BY 2.0

So things have come a long way in the forty odd years since I published my PhD work (Cannon, 1984, 1985, 1986). However, there is till a need for good old-fashioned field work: scientists putting on their wellies and getting out in the fields to study insects under natural conditions, to try to understand their ecology and behaviour.

Finally, a short section on ants and aphids!

Farm them don’t harm them!

Some organisms have learned to embrace aphids and put them to good use; in a word, they farm them! Aphids feed on phloem sap by plugging their mouthparts into phloem vessels, and the sugary liquid is forced out of the anus of the insects, allowing them to rapidly process the large volume of sap required to extract nitrogen, which present at low concentrations.

Aphids produce huge amounts of honeydew, when measured on a field scale, e.g. per hectare, although the quantities excreted per aphid are relatively small. For example black bean aphids, Aphis fabae, produce about 110 µg of sugary-rich honeydew, per aphid, per hour feeding on beans (Fischer et al., 2005).

Ants such as the black garden ant, Lasius niger collect honeydew from aphids, and in return for this gift, remove any predators, such as ladybirds, that might be tempted to feed on the aphids! This arrangement between ants and aphids is usually described as a mutualistic relationship – i.e. where both species benefit from each other – but it is not always so nicely balanced. Aphids do not always benefit from the presence of ants which can reduce the dispersal ability of the aphids (e.g. Tegelaar et al., 2012).

Are the aphids being held by the ants against their will? Probably not!

Links

https://influentialpoints.com/Gallery/Metopolophium_dirhodum_Rose-grain_aphid.htm

References

Adams, M. D., Celniker, S. E., Holt, R. A., Evans, C. A., Gocayne, J. D., Amanatides, P. G., … & Saunders, R. D. (2000). The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science, 287(5461), 2185-2195.

Cannon, R. J. C. (1984). The development rate of Metopolophium dirhodum (Walker)(Hemiptera: Aphididae) on winter wheat. Bulletin of entomological research, 74(1), 33-46.

Cannon, R. J. C. (1985). Colony development and alate production in Metopolophium dirhodum (Walker)(Hemiptera: Aphididae) on winter wheat. Bulletin of entomological research, 75(2), 353-365.

Cannon, R. J. C. (1986). Summer populations of the cereal aphid Metopolophium dirhodum (Walker) on winter wheat: three contrasting years. Journal of applied ecology, 101-114.

Dewar, A. M., Woiwod, I., & de Janvry, E. C. (1980). Aerial migrations of the rose‐grain aphid, Metopolophium dirhodum (Wlk.), over Europe in 1979. Plant Pathology, 29(3), 101-109.

Fischer, M. K., Völkl, W., & Hoffmann, K. H. (2005). Honeydew production and honeydew sugar composition of polyphagous black bean aphid, Aphis fabae (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on various host plants and implications for ant-attendance. European Journal of Entomology, 102(2), 155-160.

Gandrabur, E., Terentev, A., Fedotov, A., Emelyanov, D., & Vereshchagina, A. (2023). The Peculiarities of Metopolophium dirhodum (Walk.) Population Formation Depending on Its Clonal and Morphotypic Organization during the Summer Period. Insects, 14(3), 271.

Heathcote, G. D. (1979). Were we invaded by greenfly? Trans. Suffolk Nat. Soc. 18 part 2. pp 144-

Loxdale, H. D., Balog, A., & Biron, D. G. (2020). Aphids in focus: unravelling their complex ecology and evolution using genetic and molecular approaches. Biological Journal of the Linnean society, 129(3), 507-531.

Schaefer, G., Bent, G., & Cannon, R. (1979). The green invasion : plague of aphids in central and SE England, August 1979]. New Scientist, 83.

Tegelaar, K., Hagman, M., Glinwood, R., Pettersson, J., & Leimar, O. (2012). Ant–aphid mutualism: the influence of ants on the aphid summer cycle. Oikos, 121(1), 61-66.

Vereshchagina, A. B., & Gandrabur, Y. S. (2021). Development of Autumnal Generations and Oviposition in Metopolophium dirhodum Walk.(Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha: Aphididae). Entomological Review, 101(8), 1024-1033.

Williams, I. S., & Dixon, A. F. (2007). Life cycles and polymorphism. Chapter 3 in Emden, H. V., & Harrington, R. (Eds.). (2017). Aphids as crop pests. Cabi.

Zhu, B., Rui, W., Hua, W., Li, L., Zhang, W., & Liang, P. (2024). A-to-I RNA editing of CYP18A1 mediates transgenerational wing dimorphism in aphids. eLife, 13.

Zhu, B., Wei, R., Hua, W., Li, L., Zhang, W., Liang, P., & Gao, X. (2022). A high-quality chromosome-level assembly genome provides insights into wing dimorphism and xenobiotic detoxification in Metopolophium dirhodum (Walker). (Preprint)

Hello Ray,

I found your aphid article interesting.

Do you happen to know if there are large aphids in the UK that could be mistaken for a Giant Willow Aphid? I ask because on 25th December I took a poor photo of a large aphid on a fence post beside the Humber (quite near a pond) and assumed it was a Giant Willow Aphid.

Kind regards

Dick

Well it might have been a Giant Willow aphid I suppose? Black spruce bark aphids (Cinara piceae) are supposed to be quite large (5-6mm in length) but I haven’t seen one!😆

Thanks Ray. I dont think mine was a Black Spruce Bark Aphid which has red and black striped legs. However I have learnt something new which is good.

Regards

Dick

A very dedicated blog post. So it’s thanks to the aphids that you have a Ph(i)D. 😉 I was always fascinated by the life cycles of parasites. My favourite one is the life cycle of the lancet liver fluke (Dicrocoelium dendriticum). Mother Nature is so amazing, isn’t it?

Dicrocoelium dendriticum: I looked it up, what an extraordinary life cycle, involving snails, ants and cattle! Best regards, Ray

[…] © Ray Cannon’s nature notes […]