Insects need to time their development to the availability of resources: grow when the nutrients are flowing, rest when their supply dries up. Aphids are masters of adapting their life cycles to the growth stages of plants and trees. Here we look at how two species on sycamore trees deal with a slow-down in growth and photosynthesis during the summer months when the nutrient quality of the leaves declines.

Two species commonly occur on the undersides of sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) leaves: the Common Sycamore Aphid (Drepanosiphum platanoidis); and the Sycamore periphyllus aphid (Periphyllus acericola); there may be other species of well (see here). Drepanosiphum platanoidis is probably the most common aphid on sycamore and readily colonises new leaves in the spring (below) when the phloem sap is flooding into the unfurling leaves (See previous blog: Sycamore aphids on buds and new leaves).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

However, by the time of the second-generation, the Drepanosiphum platanoidis aphids are feeding on more mature leaves (see below) and often cease reproduction and enter a period of aestivation, a sort of summer dormancy. This period of slow-down can last anywhere between four to eight weeks (depending on the degree of maternal crowding), before reproduction starts up again in late summer. Although these aestivating aphids are in a state of reproductive dormancy, they can fly off if threatened. Unlike the other species discussed below.

The third generation consists of winged males and wingless oviparae (i.e. egg-laying females), which lay overwintering eggs after mating. The proportion of sexual individuals increases in subsequent generations.

The Sycamore periphyllus aphid, Periphyllus acericola, which may share the same leaves with the Common Sycamore aphids, look very different, being much darker (see below).

These two aphids have completely different strategies in the summer. In late May, Periphyllus acericola adults start producing rather different looking first instar nymphs, called dimorphs (see below), probably in response to declining soluble nitrogen concentrations in the phloem.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

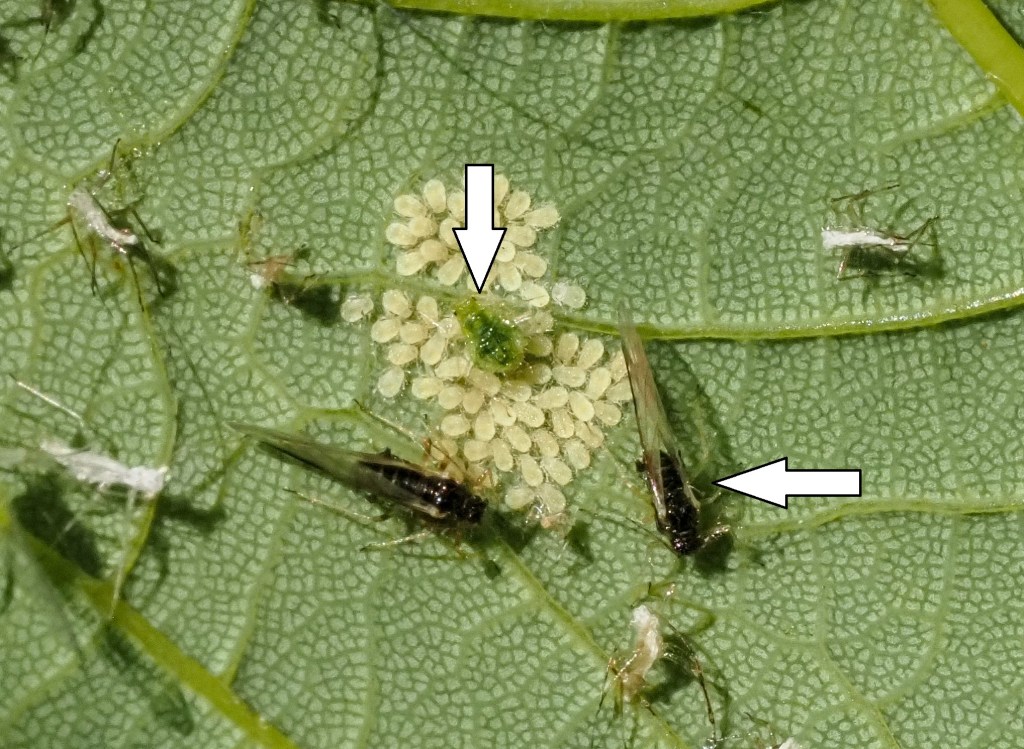

These dimorph, or dimorphic, aphids are rather flattened, yellowish-white in colour, with long, pointed hairs. They do not develop very much at first, but aestivate through the summer. They aggregate in dense groups (see below) which from a distance, look like whitish spots on undersides of leaves.

I think there is something rather appealing about these little groups of young aphids, which seem to be attended by the winged adults in some cases (below). Almost like a creche! However, I don’t know if offspring by more than one parent aggregate together; I’m inclined to think that they do, given the size of some dimorph groups.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

However, the dimorphs are somewhat vulnerable as they are small, juicy and unable to fly off! As a consequence, they get predated (fed upon) by a variety of other insects, and their numbers can show a steady decline through the summer.

The Periphyllus acericola dimorphs do not feed, and avoid moisture loss by being flat, staying close together and being covered by long hairs. When the aestivating groups eventually break up in late summer, the surviving nymphs became very active, resume development, and eventually become wingless adults.

I came across a couple of predators which were getting ‘stuck into’ (feeding) on the dimorphs at the end of May this year. How were they going to survive the summer! A lot are going to get eaten!

The other predator I managed to photograph, feeding on both nymphs and adults, was a minute pirate bug (Anthocoridae).

On a final note, aphid biologists Dransfield and Brightwell have written on their web-page for Periphyllus acericola that sycamore leaves often have numerous patches of cream or white galls (called erinea) caused by the Sycamore felt gall mite, Aceria pseudoplatani (see below). I’ve often wondered what these were!

The erinea are said to be hairy and likely to be very unpalatable to predators, and quite similar in appearance to the diapausing aphid dimorph colonies. Dransfield and Brightwell suggest that the clusters of dimorphs may have evolved to mimic the appearance of the erinea and thus, escape the attentions of of predators? I will leave you, dear reader, to decide if they look sufficiently similar? I’m inclined to think that the predators would soon spot the difference when they got close.

To conclude: these two species have evolved two different strategies. One, the Common Sycamore Aphid (Drepanosiphum platanoidis) relies on escape: the adults have wings and can fly off. The other, the Sycamore periphyllus aphid (Periphyllus acericola), relies on laying enough nymphs to satiate any would-be predator; hoping that enough of their precious, strange-looking dimorphic nymphs survive the summer. Both strategies clearly work, as these species have been around for millions of years. However, I expect they suffer variable amounts of mortality in different years, and the dimorphs are clearly an important food resource for a range of other, predatory insects. There is however, a lot more to find out about the ecology of both aphid species.

References

Chakrabarti, S., Mandal, A. K., & Saha, S. (1987). Key to Indian species of Periphyllus including four new species and hitherto unknown morphs from North‐west Himalaya (Homoptera: Aphididae). Systematic entomology, 12(1), 7-21.

Dransfield, R.D., Brightwell, R. InfluentialPoints dot com. (https://influentialpoints.com/Gallery/Periphyllus_acericola_Sycamore_Periphyllus_Aphid.htm)

Gange, A. C. (1996). Positive effects of endophyte infection on sycamore aphids. Oikos, 500-510.

Heie, O. E. (2009). Aphid mysteries not yet solved (Hemiptera: Aphidomorpha). Aphids and other Hemipterous insects, 15, 49-60.

Leather, S. (2021). https://simonleather.wordpress.com/tag/periphyllus-acericola/

Data I’m never going to publish – factors affecting sycamore flowering and fruiting patterns

Periphyllus acericola. Sycamore periphyllus aphid.

Wellings, P. W., Chambers, R. J., Dixon, A. F. G., & Aikman, D. P. (1985). Sycamore Aphid Numbers and Population Density: I. Some Patterns. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 411-424.