This summer I got a bit obsessed with whirligig beetles, spending hours lying on the banks of lakes and ponds with my camera, trying to capture their enigmatic movements. The patterns they create on the water surface are almost as interesting as the biology of the beetles themselves. At least I think so, and I hope you dear reader, will as well!

Whirligig beetles (Coleoptera family Gyrinidae) are small, less than a centimeter in the case of European species (typically 5 to 7.5 mm), but what they lack in stature, they make up for in speed and agility! Agility in, or on, a two-dimensional world. Swimming, more like skating, quickly and easily across the water; borne by the forces arising from surface tension. Their short flat legs propelling them along like little boats.

The propulsive efficiency of the swimming legs is believed to be the highest measured for a thrust-generating apparatus within the animal kingdom. (Voise & Casas, 2010).

Whirligigs commonly occur in both lentic (still) and lotic (flowing) aquatic ecosystems. Although, they usually swim and hunt for food on the water surface, things such as drowning insects or other small arthropods caught in the surface film, they can also dive down into the depths if necessary. There may be ample supplies of food items below the water surface, like copepods (see below), which I assume that they can catch?

They can however, swim ten times faster on the water surface due to the much lower frictional drag when they are only half submerged; and if conditions become too challenging – perhaps the pond dries up – they can always fly off to another site.

Whirligigs can occur in groups ranging from just a few individuals, to several thousand, especially in areas protected from the wind, often near the shore.

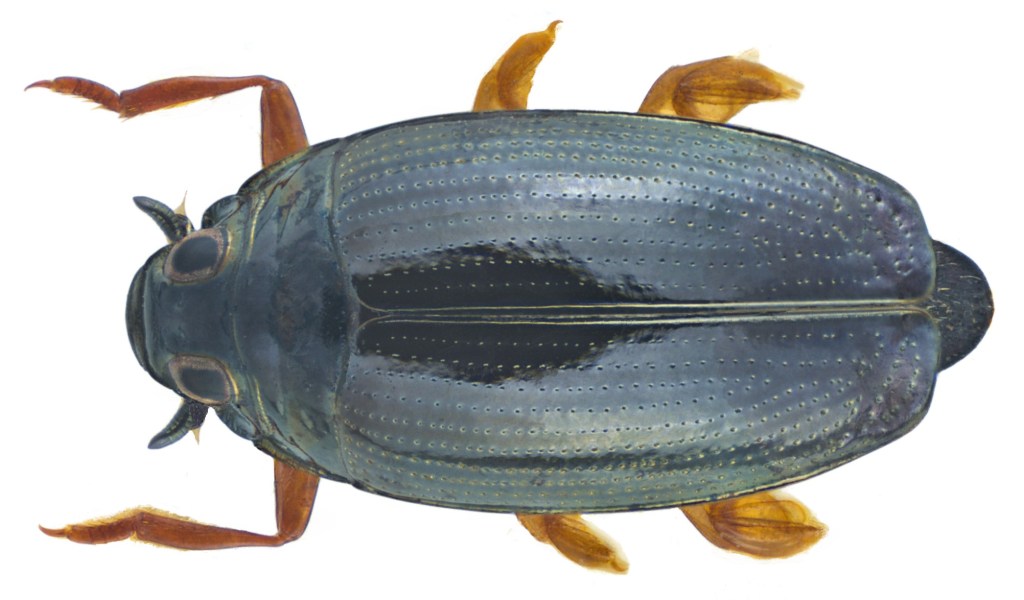

There are only 12 species in the UK and they all look rather similar, with a small, plate-like pygidium poking out at the back (i.e. the last abdominal segment at the posterior end). In fact, they are difficult to separate without examining their genitalia, which is impossible while hovering above them with a camera! Fortunately, there are some wonderful close up pictures which photographers have made available via the Creative Commons. Like this beautiful image by Udo Schmidt (below).

The zigzag swimming motion of whirligig beetles may serve to confuse predators. Whirligigs can swim extremely fast, with short bursts of speed up to 144 cm/s (>5 km/hr), which is as fast as the burst swimming speed of some fish. Their paddle-shaped middle and hind legs can beat at up to 60 times a second to propel them in these high speed bursts. In my experience, they usually swim, or skate about at a fairly moderate rate most of the time, with occasional bursts of high speed action, often when they interact with other individuals.

Masters of the interface

When searching for floating prey items – they must spend their lives waiting for something tasty to drop from the sky – they investigate anything that catches their eye. In fact they have four eyes – two below and two above the water surface – as this amazing photograph shows here – and in the image from the Biological museum of Lund University in Sweden (below).

I noticed that they often, repeatedly checked out the same floating piece of fluff or plant seed, coming back time and again to see whether it was edible. There is sometimes a considerable amount of detritus on the water surface.

They are also masters of their element, responding to any ripples or waves caused by other animate life on the water surface. This must also include complex interactions with other species (such as pond skaters), conspecific individuals (below left) and members of the opposite sex.

Whirligig beetles whirl, i.e. they swim in circles and their circular motions may be a way of generating surface waves for ‘echolocation’, perhaps we should call it ripple rebound. Their tiny brains must be particularly adept at sorting out all the different wave patterns which they generate and receive. Just how complicated these patterns are is illustrated by photographs taken at high shutter speeds, 1/3200 in this case (see below).

It is possible that their characteristic movement patterns which they create when disturbed or alarmed, are a form of aposematic signalling. The conspicuous ripples and eddies (below) may be a way of warning any would be predator that, hey ‘I taste really nasty’!

Advantages in group living

In North America, whirligig beetles often come together in huge rafts comprising hundreds or thousands of individuals. During the night, the beetles disperse to other nocturnal foraging sites, but once again come together in dense aggregations before daylight. They are thought to be relatively safe from predation in these large rafts, partly because they produce strong-smelling defensive secretions which render them rather distasteful to fish that might otherwise eat them. However, not all gyrinids produce these defensive compounds (containing gyrinidal, which smells slightly like sour apples) so the picture is, as ever in biology, more complex.

There are also distinct benefits to be had from swarming: large groups of whirligig beetles are better at avoiding predators than small groups, or single individuals. Large groups of insects simply have more eyes with which to scan the environment and detect any potential predators, and individuals within the group can respond rapidly to the defensive movements of their neighbours. The strong-smelling defensive secretions an individual produces in response to the sight of a predator (‘fish!, fish!) may also act as an alarm substance, warning the other whirligigs in the immediate vicinity as well as repelling the fish.

Whirligig beetles (Gyrinidae), have been spinning about on water surfaces on this planet for over 250 million years. During this vast span of time they have remained relatively unchanged, specialised in moving efficiently on the water surface and collecting small arthropods caught in the surface film. Unlike many other creatures, they survived the “Great Dying” (Permian-Triassic mass extinction event) and much later on became the dominant whirligig beetle fauna, following the end Cretaceous extinction event (c. 66 million years ago). I think that this evolutionary stability and longevity deserves enormous respect, especially from an organism like ourselves (H. sapiens) that has only been around for a few hundred thousand years and is making a good job of messing up the planet for everything else!

All of my photographs were taken during July and August at Felmersham Gravel Pits SSSI.

References

Gustafson, G. T., Prokin, A. A., Bukontaite, R., Bergsten, J., & Miller, K. B. (2017). Tip-dated phylogeny of whirligig beetles reveals ancient lineage surviving on Madagascar. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 8619.

Härlin, C. (2005). To have and have not: volatile secretions make a difference in gyrinid beetle predator defence. Animal behaviour, 69(3), 579-585.

Heinrich, B., & Vogt, F. D. (1980). Aggregation and foraging behavior of whirligig beetles (Gyrinidae). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 7, 179-186.

Henrikson, B. I., & Stenson, J. A. (1993). Alarm substance in Gyrinus aeratus (Coleoptera, Gyrinidae). Oecologia, 93(2), 191-194.

Meinwald, J., Opheim, K., & Eisner, T. (1972). Gyrinidal: a sesquiterpenoid aldehyde from the defensive glands of gyrinid beetles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 69(5), 1208-1210.

Voise, J., & Casas, J. (2010). The management of fluid and wave resistances by whirligig beetles. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 7(43), 343-352. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2842614/

Vulinec, K., & Miller, M. C. (1989). Aggregation and predator avoidance in whirligig beetles (Coleoptera: Gyrinidae). Journal of the New York Entomological Society, 438-447.

Yan, E.V., Beutel, R.G. & Lawrence, J.F. Whirling in the late Permian: ancestral Gyrinidae show early radiation of beetles before Permian-Triassic mass extinction. BMC Evol Biol 18, 33 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1139-8

Great article! It’s nice to see such a thorough post on these fascinating beetles.