Bumblebees come in a range of sizes and colours: there are over 270 Bombus species in the world, and 24 occur in the UK (see here). They are I think, among the most beautiful insects, probably because they are a friendly round shape, covered in soft hairs of many colours. Some look like little woolly bears! (See below). It might come as a bit of a surprise then, to know that some of them are called thieves and robbers! How come? It’s all to do with the length of their tongues!

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Bumblebee species differ in their ability to forage on different flowers, which is related to the length of their proboscises, or tongues. Flowers come in all shapes and sizes of course, but the length of a bee’s tongue determines how easily it can reach the floral nectaries exuding the nectar. Too short a tongue, and they will not be able to access the nectar in some of the deeper flowers. Too long, and it might become less efficient to use on small, open flowers.

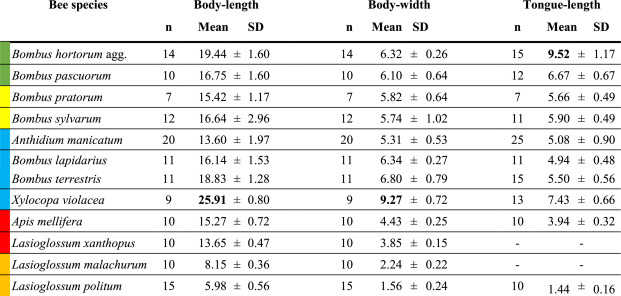

Here is a list of bumblebee tongue lengths from an academic paper. These measurements can vary in detail, but the garden bumblebee, Bombus hortorum usually comes top of the list with the longest tongue (see below); here is another list of bumblebee tongue lengths.

Here is a photograph of a garden bumblebee with its long tongue extended (below). Bombus hortorum, has one the longest tongues which can reach just over 2 cm when fully extended (see below). Long-tongued species such as this tend to take nectar from flowers that cannot be accessed by other foragers due to their shorter tongue length. A longer proboscis is also often associated with a narrower body, which helps the bumblebees to squeeze themselves into flowers with deep-lying nectaries.

We use the word tongue as a shorthand way of referring to the proboscis, which a composite structure made up of labial palps and galea which form a tube surrounding the glossa (or true tongue) to extract nectar. The tongue is rather like a brush, being covered by elongated papillae that open up when immersed in the fluid and the bee laps up the nectar by capillary action and then sucks it up into its body. There’s a very thorough description here: Hey Bee, Stick Out Your Tongue and Say “Ahh”

The bumblebee proboscis is both strong and flexible, and can even be used to stab a hole in a leaf, as shown below.

But bumblebees also have mandibles which they can use to chew holes in flowers if they need to! Here is a buff-tailed bumblebee using holes made in a Salvia flower to access the nectar. Each flower has a round hole near the base made by a nectar robber.

Nectar robbing occurs when bees either bite through the base of a flower to ‘steal’ the nectar (primary robbing) or use holes made by previous ‘robbers’ (secondary robbing). Given that bumblebees regularly revisit a rewarding patch of flowers, they will no doubt use the holes time and again. Nectar robbers circumvent the floral opening, often removing nectar without coming into contact the anthers and/or stigma.

Bumblebees who have tongues which are long enough to access the nectar via the corolla, or flower tube, are called legitimate foragers. Clearly, the nectar robbers are not helping to pollinate the flower, so it represents a form of ‘cheating’ in that it disrupts the mutualistic relationship between plants and pollinators. However, more recent research has revealed that robbers do sometimes pollinate the plants that they visit, so like most things in nature, it is complicated.

I took some photographs of the garden bumblebee, Bombus hortorum, nectaring on some Salvia flowers in a legitimate way (see below), which I also described in a previous blog entitled Red hot lips and bumblebees. They are sucking up the nectar by poking their proboscis straight down the flower, not by biting holes in the base of the flower!

Buff-tailed bumblebees (Bombus terrestris) are well-known nectar thieves, because of their relatively short tongue (see below). They can learn this behaviour from one another, i.e. social transmission, and other species can also pick up on this behaviour and use the holes created by the original nectar robbers.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Long-tongued bumblebees generally forage significantly faster on flowers with long corolla tubes than shorter-tongued species, which may not even be able to access these sort of flowers at all. Thus, bumblebees with long tongues (or proboscises) prefer flowers with longer calyx tubes, such as foxgloves, honeysuckle and comfrey, and these deeper tubed flowers often produce more nectar than short-tubed ones.

Here is a Buff-tailed bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) nectaring with its head down on a Salvia flower. There must be a hole in the base of the flower, probably made by a previous visitor.

The buff-tailed bumblebees almost seem to be hugging the Salvia flowers as they insert their tongues into holes at the base of the floral tubes (see below).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

A long proboscis can be a bit of a hindrance sometimes, when it comes to collecting nectar from short-tubed flowers. Although, long-tongued bees can usually manage to imbibe nectar from short-tubed flowers, this occurs less frequently, because of the increased handling time involved. Foraging is probably most efficient when the length of a bee’s proboscis matches, or slightly exceeds, the depth of the corolla tube.

In conclusion, bumblebees are flexible and can change their behaviour in response to the availability of floral rewards, and the level of competition between other bumblebee species. If they cannot access the nectar by legitimate means, they can always turn to thieving!

References

Balfour, N. J., Garbuzov, M., & Ratnieks, F. L. (2013). Longer tongues and swifter handling: why do more bumble bees (Bombus spp.) than honey bees (Apis mellifera) forage on lavender (Lavandula spp.)?. Ecological entomology, 38(4), 323-329.

Irwin, R. E., Bronstein, J. L., Manson, J. S., & Richardson, L. (2010). Nectar robbing: ecological and evolutionary perspectives. Annual review of ecology, evolution, and systematics, 41(1), 271-292.

Lechantre, A., Draux, A., Hua, H. A. B., Michez, D., Damman, P., & Brau, F. (2021). Essential role of papillae flexibility in nectar capture by bees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(19), e2025513118.

Leadbeater, E., & Chittka, L. (2008). Social transmission of nectar-robbing behaviour in bumble-bees. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275(1643), 1669-1674.

Maloof, J. E., & Inouye, D. W. (2000). Are nectar robbers cheaters or mutualists?. Ecology, 81(10), 2651-2661

Silló, N., & Claßen-Bockhoff, R. (2024). A multitude of bee pollinators in a phenotypic specialist-pollinator diversity from the plant’s perspective. Flora, 312, 152461.

Excellent post, and great information! I had thought I had Carpenter Bees drilling holes in my salvia, but I’d better look again at the photos – they may have been honeybees, as you describe here. And now I understand better why the hummingbirds would chase away the bees!

Thank you.😃 Some studies have shown that it is the more experienced honeybee foragers that tend towards nectar robbing. Or are they just older and wiser?!

Very interesting post, Ray. I wasn’t aware of their criminal nature. They’re such adorable woolly robbers, aren’t they? 😍🐝

Thanks. There is one theory, that rectar robbing has a neutral, rather than a negative effect. Although the nectar robbers’ can damage or destroy the corollas of flowers, they don’t touch the sex organs or destroy the ovules. So, their behaviour may not affect the fruit sets or seed sets of the host plant, as long as there are some legitimate foragers feeding on nectar in the ‘proper’ way.😄

[…] The second species to arrive was Bombus hortorum; it established a bridgehead in the 1950s. The interesting thing about the Garden bumblebee is that it has a long tongue (or proboscis), which gives it access to the nectar in some flowers which other bumblebees cannot reach, as least not without a little subterfuge! See previous blog: Two ways to suck a Salvia! Nectar robbing bumblebees. […]