The mating behaviour of Odonata is highly diverse, but most species are promiscuous (polygamous), and both sexes usually mate several times over the course of their lives (Cordero‐Rivera et al., 2023). Nevertheless, sexual conflicts between males and females frequently arise, for the simple reason that the optimum number of matings is usually different for either sex (see Cannon, 2023).

Sexual conflict takes the form of extensive mating harassment by males; i.e. unwanted attention that can cause injuries to the females and exposes them to toxins and sexually transmitted diseases (Chauhan et al., 2016). Females generally prefer to mate less than males because they have other things to do! Most importantly, the production and deposition of eggs, even though males are often involved in guarding ovipositing females in some species.

Female polymorphism – the occurrence of two or more different female morphs or forms – is common in coenagrionid damselflies and has been described in more than 100 species, e.g. in the genera, Argia, Coenagrion, Enallagma, and Ischnura. Typically, one of the female morphs resembles the male and is called the andromorph (or androchrome), while the other female morphs are called heteromorphs (or gynochromes).

Andromorph females look, and behave, a lot like males; whereas the gynomorph females exhibit a more cryptic colouration and behaviour, often remaining hidden amongst the vegetation. Scientists have studied female-specific colour polymorphism in damselfly species in the genus Ischnura and have come to the conclusion that it has evolved as a way of reducing harassment by males.

The polymorphism, is therefore, maintained by sexual selection, with two main competing explanations. In the male mimicry (MM) hypothesis, andromorphic females escape harassment by mimicking the appearance of males. In the alternative, learned mate recognition (LMR) hypothesis, harassment of both morphs will be negatively frequency-dependent: males learn to recognise mates based on which female morph is most common in their population, and as a consequence, harassment is greatest for the commonest morph.

However, the prediction that the existence of polymorphic females reduces overall harassment of females has rarely been tested (Xu & Fincke, 2011). So the key question remains: Did the polymorphism evolve as a way of avoiding, or at least reducing harassment by males?

Harassment

To recap, the presence of differently coloured female morphs is generally considered to indicate the existence of alternative reproductive strategies, which have evolved as a result of sexual conflict over mating.

So-called naïve males start out with an innate preference for androchrome morphs, but this is usually lost after successive interactions with gynochrome females (Sánchez-Guillén et al., 2013). Thus, mature males either lack of a preference, or have a preference for gynochrome females.

Males develop search images for the most common morph, which is then disproportionately targeted. In other words, they learn to recognise and search for the most common type of female in the population, which places the other, rarer morphs at an advantage. However, male preferences will change in response to any variations in the relative frequencies of the female morphs, i.e. the ratio of andro- to gynomorphs.

The rarer female morphs benefit in terms of higher fecundity because they experience lower levels of male mating harassment (Svensson et al. 2005; Iserbyt et al. 2013). However, the overall intensity of male harassment can increase when there are higher numbers of males, either in absolute terms (population) or relative to the number of females; (i.e. the operational sex ratio). Interactions between males and females simply occur more frequently in both of these situations.

“selection through sexual conflict over the frequency of matings has selected for polymorphic females to reduce the overall intensity of male mating harassment” (Sánchez-Guillén et al., 2020).

The different morphs or forms

As we have seen, one female morph closely resembles the male of the same species in terms of body colouration (see below). These andromorphs are, at least from a human perspective, nearly identical; i.e. they are functional mimics, similar in both patterning and coloration. Consequently, they are less attractive to males and, therefore, receive lower rates of sexual harassment by mate-searching males (Van Gossum et al., 2011). Indeed, males are probably incapable of distinguishing between andromorph females and other males in most situations (Gossum et al., 2005).

In the Blue-tailed damselfly, Ischnura elegans, adult females occur in three colour morphs, and these female colours are inherited as one autosomal locus with three alleles in a dominance hierarchy (Svensson et al., 2009). In other words, the genes (or DNA sequences) responsible for producing the three different morphs occur on a non-sex chromosome and come in three forms.

Males are monomorphic with respect to colour, meaning they are always the same colour, so the polymorphism is described as being sex-limited in its expression. Let’s take a look at the different phenotypes or expressions of these different alleles.

Females have a red (rufescens) or violet (violacea) thorax when immature, and turn into three distinct sexually mature morphs: coloured blue (the androchrome form typica), olive-green (infuscans) or olive-brown (obsoleta also called rufescens-obsoleta) (Henze et al., 2019). For an excellent illustration of the colour forms showing how they change from one to another, see here and here (on John Curd’s Odo-nutters website).

Photo by Aurélien Baudoin Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Photo by scarabaeus_58 Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0

Photo by gailhampshire Flickr CC BY 2.0

In the two separate female forms, infuscans and obsoleta, the abdominal segment no. eight is usually brown, i.e. not blue, as in the males and androchrome females. Pink rufescens individuals (shown below) change into the rufescens-obsoleta morphs and lose the blue tail marking on segment 8.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon 6 June 24

The well-defined black stripe on the thorax of the other morphs is replaced by a fuzzy reddish or brownish line in rufescens and obsoleta females (Henze et al., 2019).

Photo by gailhampshire Flickr CC BY 2.0

Immature female violacea forms (below) mature into either greenish infuscans (below) or the male like androchrome form typica.

Photo by u278 Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Males start out a light green colour (below), then develop a blue ‘tail’ (on segment S8).

Photo by Paul Ritchie Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Males gradually gradually turn blue on their thorax and the underside of the first couple of abdominal segments, as well as the blue ‘tail’ (first and second photos below).

Photo by Paul Ritchie Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Photo by Frank Vassen Flickr CC BY 2.0

Whilst andromorphs escape excessive harassment from males they also run the risk of missing out on mating altogether, and some do not even manage to secure a single copulation (Van Gossum et al., 2011). However, “both morphs [i.e. andromorphs and gynomorphs] are equally successful in avoiding unwanted matings, even if they use different tactics to do so” (Fincke, 2004). For example, by hiding in the vegetation. However, to avoid harassment by males and to escape supernumerary matings, females must interrupt what they are doing, such as resting, thermoregulating, foraging, or ovipositing (Fincke, 2004), which comes at a cost for females. It is these factors which presumably drive the evolution of the different forms.

Mating

Although the sperm obtained from one mating is probably enough to fertilise all of the eggs a female could deposit, most females mate multiple times. However, androchrome females are generally less polyandrous than gynochrome females.

Male damselflies transfer sperm from their primary genitalia – located near the tip of the abdomen in segment 9 – to their secondary or accessory genitalia, which are located near the front of the abdomen (on the ventral side of the second and third segments). [It’s a good job human males don’t have to do this!😂]

Males can carry out this sperm transfer whilst clasping the female with their claspers at the back of her neck. See previous blogs here and here.

“Species of the genus Ischnura copulate for longer than other odonates, but generally do not exhibit post-copulatory mate guarding” (Cooper et al., 1996).

Mating begins with the male grasping the female, followed by the tandem flight.

It is said that damselflies can recognise each other as being of the same species, during mating, by means of tactile interactions, i.e. between the male abdominal appendages and female mesostigmal plates of the: she can then accept mating, or refuse to cooperate with the male (Wellenreuther & Sánchez‐Guillén, 2016).

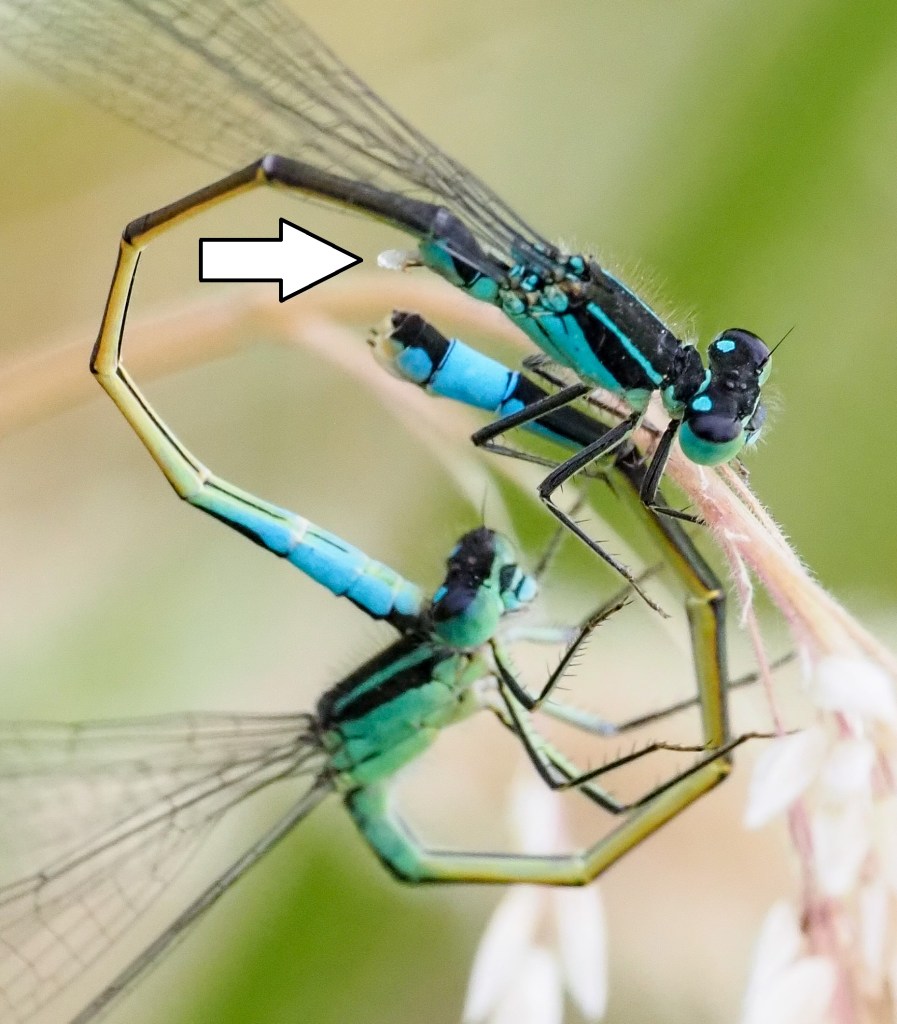

Soon after the tandem is formed, if the female is receptive, she bends her abdomen up towards secondary genitalia of the male, and the copulation takes place in the typical wheel position (below).

In Ischnura elegans the male uses his genital appendages (paraprocts) to clasp the female, and they can remain in tandem for five hours or more, until the tandem splits and the female flies off (unaccompanied), to lay the eggs (Miller, 1987). The closing of the paraproctal claspers on the neck of the female is mainly passive, caused by elastic protein (called resilin) in the cuticle of the paraproctal bases.

“both structures – the male claspers and the female prothoracic hump – function together like a snap-fastener.” (Willkommen et al., 2015).

Female Ischnura elegans damselflies can however, actively resist a male’s mating attempt, and free herself from the tandem position (below), by “shaking her body at a high frequency along the right–left axis”, sometimes causing the male to turn upside-down! (Xu & Fincke, 2011).

In 2024, I managed to capture a photo of a pair of Blue-tailed damselflies just as they were breaking apart from a mating wheel. [I cannot be sure, but it is possible that my presence with a macro lens induced this termination]. Nonetheless, it is possible to see what looks like the male penis with a small white blob attached (see below). So, it is possible that the male was engaged in sperm removal from the female, as males use their penis to remove sperm deposited in the female’s sperm storage organs from previous matings (as well as to transferring their own sperm to the female) (Waage, 1979).

“In general, male damselflies are able to remove sperm from the female genitalia” (Cordero-Rivera et al., 2023).

Researcher, P. L. Miller of Oxford University wrote, that after the stored sperm of previous males was removed from the female’s bursa, it was clasped between the hooks and folded horns of the male’s penis (see here), and was finally withdrawn at the end of copulation (Miller, 1987). So, the white blog in the photo (above) may be the sperm contribution of another male (a previous lover!). What does the male do with it, I wonder?

Photo by Ouwesok Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0

There are at least six Ischnura species, which are trimorphic, i.e. with the three colour morphs (androchrome, aurantiaca and infuscans) in the Palaearctic region: I. elegans, I. e. ebneri, I. evansi, I. fountaineae, I. genei, I. graellsii and I. saharensis (Sánchez-Guillén et al., 2020). They are all highly polyandrous (i.e. promiscous), e.g. with an average of about six matings in gynochromes of I. elegans (Sánchez-Guillén et al. 2013). It is thought that the same phenotypic morphs have evolved multiple times via convergent evolution, suggesting that different species in this genus have experienced similar selective pressures in the past. However, it is, of course, impossible to go back and measure the harassment rates from ancestral populations! (See Xu & Fincke, 2011). Nevertheless, harassment by males appears to have driven the evolution of two or more different female forms in Ischnura damselflies.

There is even more to this story, as the different female morphs also differ in terms some other phenotypic traits, besides colouration, including resistance and tolerance to parasitic mites, cold tolerance, larval developmental times and more (Svensson et al., 2020). Therefore, the different female morphs are subject to selective forces other than just male mating harassment, and factors such as climate and and the prevalence, and virulence, of parasites also affect the variation in morph frequencies across the large geographical range of I. elegans (Willink et al., 2021).

There is a lot more to learn about the biology of these beautiful damselflies, the females of which come in ‘coats’ of many colours!

References

Berenbaum, M. (2018). Damselflies in Distress. American Entomologist, 64(1), 3-6.

Blow, R., Willink, B., & Svensson, E. I. (2021). A molecular phylogeny of forktail damselflies (genus Ischnura) reveals a dynamic macroevolutionary history of female colour polymorphisms. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 160, 107134.

Cannon, R. J. (2023). Courtship and Mate-finding in Insects: A Comparative Approach. CABI.

Chauhan, P., Wellenreuther, M., & Hansson, B. (2016). Transcriptome profiling in the damselfly Ischnura elegans identifies genes with sex-biased expression. BMC genomics, 17, 1-12.

Cooper, G., Holland, P. W. H., & Miller, P. L. (1996). Captive breeding of Ischnura elegans (Vander Linden): observations on longevity, copulation and oviposition (Zygoptera: Coenagrionidae). Odonatologica, 25 (3), 261-273.

Cordero‐Rivera, A., Rivas‐Torres, A., Encalada, A. C., & Lorenzo‐Carballa, M. O. (2023). Sexual conflict and the evolution of monandry: The case of the damselfly Ischnura hastata (Odonata: Coenagrionidae) in the Galápagos Islands. Ecological Entomology, 48(3), 336-346.

Fincke, O. M. (2004). Polymorphic signals of harassed female odonates and the males that learn them support a novel frequency-dependent model. Animal Behaviour, 67(5), 833-845.

Gosden, T. P., Stoks, R., & Svensson, E. I. (2011). Range limits, large-scale biogeographic variation, and localized evolutionary dynamics in a polymorphic damselfly. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 102(4), 775-785.

Henze, M. J., Lind, O., Wilts, B. D., & Kelber, A. (2019). Pterin-pigmented nanospheres create the colours of the polymorphic damselfly Ischnura elegans. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 16(153), 20180785.

Iserbyt, A., Bots, J., Van Gossum, H., & Sherratt, T. N. (2013). Negative frequency-dependent selection or alternative reproductive tactics: maintenance of female polymorphism in natural populations. BMC evolutionary biology, 13, 1-11.

Miller, P. L. (1987). An examination of the prolonged copulations of Ischnura elegans (Vander Linden)(Zygoptera: Coenagrionidae). Odonatologica, 16(1), 37-56.

Piersanti, S., Salerno, G., Di Pietro, V., Giontella, L., Rebora, M., Jones, A. et al. (2021) Tests of search image and learning in the wild: insights from sexual conflict in damselflies. Ecology and Evolution, 11, 4399–4412.

Sánchez-Guillén, R. A., Ceccarelli, S., Villalobos, F., Neupane, S., Rivas-Torres, A., Sanmartín-Villar, I., … & Cordero-Rivera, A. (2020). The evolutionary history of colour polymorphism in Ischnura damselflies (Odonata: Coenagrionidae). Odonatologica, 49(3-4), 333-370.

Sánchez-Guillén, R. A., Hammers, M., Hansson, B., Van Gossum, H., CorderoRivera, A., Galicia-Mendoza, D. I., & Wellenreuther, M. (2013). Ontogenetic shifts in male mating preference and morph-specific polyandry in a female colour polymorphic insect. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 13, 116.

Sánchez‐Guillén, R. A., Wellenreuther, M., Chávez‐Ríos, J. R., Beatty, C. D., Rivas‐Torres, A., Velasquez‐Velez, M., & Cordero‐Rivera, A. (2017). Alternative reproductive strategies and the maintenance of female color polymorphism in damselflies. Ecology and Evolution, 7(15), 5592-5602.

Svensson, E. I., Abbott, J. K., Gosden, T. P., & Coreau, A. (2009). Female polymorphisms, sexual conflict and limits to speciation processes in animals. Evolutionary Ecology, 23, 93-108.

Takahashi, M., Okude, G., Futahashi, R., Takahashi, Y., & Kawata, M. (2021). The effect of the doublesex gene in body colour masculinization of the damselfly Ischnura senegalensis. Biology letters, 17(6), 20200761.

Takahashi, M., Takahashi, Y., & Kawata, M. (2019). Candidate genes associated with color morphs of female-limited polymorphisms of the damselfly Ischnura senegalensis. Heredity, 122(1), 81-92.

Tyrrell, M. polymorph in the Blue-tailed Damselfly Ischnura elegans (Vander Linden). J. of Brit. Dragonfly Society, 23(2), 33-

Van Gossum, H., Bots, J., Van Heusden, J., Hammers, M., Huyghe, K., & Morehouse, N. I. (2011). Reflectance spectra and mating patterns support intraspecific mimicry in the colour polymorphic damselfly Ischnura elegans. Evolutionary Ecology, 25, 139-154.

Waage, J. K. (1979). Dual function of the damselfly penis: sperm removal and transfer. Science, 203(4383), 916-918.

Willink, B., Blow, R., Sparrow, D. J., Sparrow, R., & Svensson, E. I. (2021). Population biology and phenology of the colour polymorphic damselfly Ischnura elegans at its southern range limit in Cyprus. Ecological Entomology, 46(3), 601-613.

Willink, B., Duryea, M. C., Wheat, C., & Svensson, E. I. (2020). Changes in gene expression during female reproductive development in a color polymorphic insect. Evolution, 74(6), 1063-1081.

Willink, B., Tunström, K., Nilén, S., Chikhi, R., Lemane, T., Takahashi, M., … & Wheat, C. W. (2024). The genomics and evolution of inter-sexual mimicry and female-limited polymorphisms in damselflies. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 8(1), 83-97.

Wellenreuther, M., & Sánchez‐Guillén, R. A. (2016). Nonadaptive radiation in damselflies. Evolutionary Applications, 9(1), 103-118.

Willkommen, J., Michels, J., & Gorb, S. N. (2015). Functional morphology of the male caudal appendages of the damselfly Ischnura elegans (Zygoptera: Coenagrionidae). Arthropod structure & development, 44(4), 289-300.

Xu, M., & Fincke, O. M. (2011). Tests of the harassment-reduction function and frequency-dependent maintenance of a female-specific color polymorphism in a damselfly. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 65, 1215-1227.

Wishing you a very happy and healthy New Year, Ray. Thank you very much for this highly informative and well-illustrated blog post. I agree: human males can indeed count themselves lucky that they do not have to transfer sperm from their primary to their secondary genitalia the way the damselflies have to. 😂

Thank you Markus for your comments and for reading my blog!

Happy New Year, Ray

Super interesting information and photos, Ray. Especially the mysterious white blob you captured in your photo.

I find myself wondering if the “male mimic” females also are more aggressive in behavior than the differently colored (perhaps more passive) females, perhaps seeking out their males instead of waiting to be discovered.

Or is all this aggression by males a form of foreplay priming the females somehow ( hormonal etc). Do odonates use pheromones at all. Do males have spermatophores or simply semen?

So many mysteries. Thank you for your wonderful work.

Just FYI, I know it is me but I have really had trouble commenting on WordPress- I think it remembers a long ago account from several decades ago (of which I have no idea of username or passwords!) This is my 5th and final attempt!

Super interesting information and photos, Ray. Especially the mysterious white blob you captured in your photo.

I find myself wondering if the “male mimic” females also are more aggressive in behavior than the differently colored (perhaps more passive) females, perhaps seeking out their males instead of waiting to be discovered.

Or is all this aggression by males a form of foreplay priming the females somehow ( hormonal etc). Do odonates use pheromones at all. Do males have spermatophores or simply semen?

So many mysteries. Thank you for your wonderful work.

Just FYI, I know it is me but I have really had trouble commenting on WordPress- I think it remembers a long ago account from several decades ago (of which I have no idea of username or passwords!) This is my 5th and final attempt!

Thank you!😁 I don’t think the andromorph (or androchrome) females that look like the males are any more aggressive. However, they can be slightly larger than the other, differently coloured females, and also more fecund (more eggs). But this difference is only apparent when they are relatively rare. Perhaps they don’t need to be aggressive because they can always avoid mating (by not stretching up their abdomen to form a wheel) but they probably have to put up with the male clasping them by the neck when they are not interested and want to get on with other important activities, like feeding, warming up in the sun, and egg laying. This is one of the ways that males harass them.

So like many (most) insects, females can say no, and in doing so, exercise a fair degree of choice about whom they mate with. This is probably why they mate more than once. Males, on the other hand, try to ‘put it about’ as much as they can (!), because the costs of mating, are lower for them, than females. Sperms are ‘cheap’ to make and they don’t have to worry about oviposition. However, in many odonata species, but not this one, the males do guard ovipositing females, but this is more about making sure she does not mate again, and lays his eggs!

In some insects, females do put up a degree of resistance as a way of testing the strength and endurance of the males. Incidentally, this also happens in vertebrates where the females lead a bunch of males in a mating chase (e.g in whales)!.

In many insects, females can also make choices AFTER she has mated, called cryptic female choice. She can use the sperms of the male she like best, even though he may not have been the latest one she mated with! It often depends on how good a performance he displayed and how loudly he sang, or how stimulated she felt!

It’s all in my (very expensive I’m afraid) academic book. I’ll have to write a more popular version.

Finally, no spermatophores in these damselflies.

Best wishes,

Ray Cannon