“Striped patterns are common in nature and are used both as warning signals and camouflage“(Barnett et al., 2017)

Have you ever noticed how some butterflies have striped antennae? Little magic wands of black and white segments topped by a bright white bulb (see below).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Last year, some colleagues and I wrote an article in the magazine of the Royal Entomological Society, Antenna, asking why some butterflies have such stripy antennae (Loxdale et al., 2024). I.e. Antennae with alternate black and white segments. We also asked the question: why do the species with stripy antennae, occur mostly – but by no means exclusively – in certain butterfly families, such as the Lycaenidae (copper, blues and hairstreaks) and the Hesperiidae (skippers)?

I can’t say that we effectively answered either of these questions (!), but the idea was to provoke some debate. We tentatively concluded that a visual phenomenon known as disruptive colouration – discussed below – was probably the most likely explanation: that by deflecting, or deterring attack, stripy antennae provide the insect with a survival advantage. But why some butterflies have them and others don’t, is a bit of a mystery.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

In this blog, I revisit some of the ideas, or hypotheses, concerning this topic, and illustrate then with photographs I have taken over the years.

If we assume that these markings are adaptive, i.e. that have, or at least had, in the past, some functional significance, let’s consider what they may have evolved for.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Firstly, its worth remembering that markings on an animal’s body may have more than one function. Indeed, butterfly bodies, and the wings in particular, are a smorgasbord of different visual devices. They can use their colours and patterns – so attractive to us – to send signals when the wings are open, or simply choose to close them and disappear into the background. I discussed this multifunctionality in a blog called: What a beauty! Different wings for different duties.

The difference between the brightly coloured upper wings and the drab lower wings (crypsis) are particularly apparent in Small tortoiseshell (Aglais urticae), shown below.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

If we include appendages – e.g. antennae, legs and ‘tails’ – in the overall visual package, these can also be brought into play for a variety of functions: such as sending warning signals, enhancing crypsis or confusing predators.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

What we see in the shapes, colours and patterns on an animal’s body are the product of a variety of different selection pressures which have shaped the evolution of the organism we are considering. Some of them may have evolved to work in concert with others, and most importantly, in combination with the behaviour of the animal in its environment. That’s why, just studying the form and structure of the body, in the absence of behaviour – i.e. how the structures are used in the life of the organism – may not deliver a complete understanding of its biology.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Bearing this in mind, what can we learn, or at least hypothesise about, butterflies that have stripped antennae? There are several hypothetical mechanisms by which they might function to conceal the organism: e.g. background matching, disruptive colouration, masquerade, self-shadow concealment, distractive marks and motion dazzle (list taken from Merilaita et al., 2017: How camouflage works).

Many of these ideas originated in the classic works by Thayer (1909) and Cott (1940). Professor Hugh Cott was a pioneer of this field of adaptive colouration, and the book he wrote on the subject was very influential, and still very readable today (Cott, 1940: here). He came up with many of the terms and categories still widely used and investigated today. For example, disruptive colouration, or disruptive camouflage, which typically involves high-contrast patches which break up the surface or edges of the organism’s body. In other words, high-contrast markings intersecting an animal’s outline effectively ‘disrupt’ the viewer’s ability to discern or detect it.

The Angle Shades moth is a good example of a lepidopteran with contrasting bands or spots, which break up the outline (below), making it harder for predators to identify and target them. The term maximum disruptive contrast is used to describe patterns where colourful patches with highly contrasting tones or hues enhance the overall visual noise by creating false edges which are more apparent to a predator, for example, than the real outline of the insect (Cuthill et al., 2019).

There is now, quite a lot of evidence to show that stripes and bands on the body of an animal, or on the wings of a butterfly, can decrease predation by acting in several possible ways, including aposematism, motion dazzle, background matching disruptive colouration (see Seymoure & Aiello, 2015).

N.B. Disruptive colouration is not to be confused with distractive markings, such as the white mark on the wings of the comma butterfly, discussed in a previous blog: Distractive markings on lepidopteran wings.

Coincident disruptive colouration

Hugh Cott identified what he called a ‘sub-principle’, or sub-category, of disruptive marking, which he termed coincident disruptive colouration. He defined it as follows:

Continuous patterns that range over different body parts and the outline between them, masking the tell-tale presence of the otherwise conspicuous appendages or other revealing body parts, such as limbs, antennae or eyes (Cott, 1940). (From Stevens & Merilaita, 2009).

Interestingly, Cott (1940) includes antennae under the category of coincident disruptive colouration, but according to Cuthill & Székely (2009), the true benefit of this type of marking lies in breaking up the shape of the body part. Personally, I find it difficult to imagine that stripy antennae do this, but we have to imagine how the butterfly appears through the eyes of a would-be predator, such as a bird. Not through our eyes!

Disruptive marginal patterns

More appealing to my mind, is the idea of disruptive marginal patterns which Cott (1940 p. 93-96 ) suggested conceal the form or contours of the animal in some ways. Cott (1940) pointed out that checkered or banded marginal configurations are found on the wing margins of many butterflies and moths. These are often located relatively near to antennae, at the front end of the butterfly (see below).

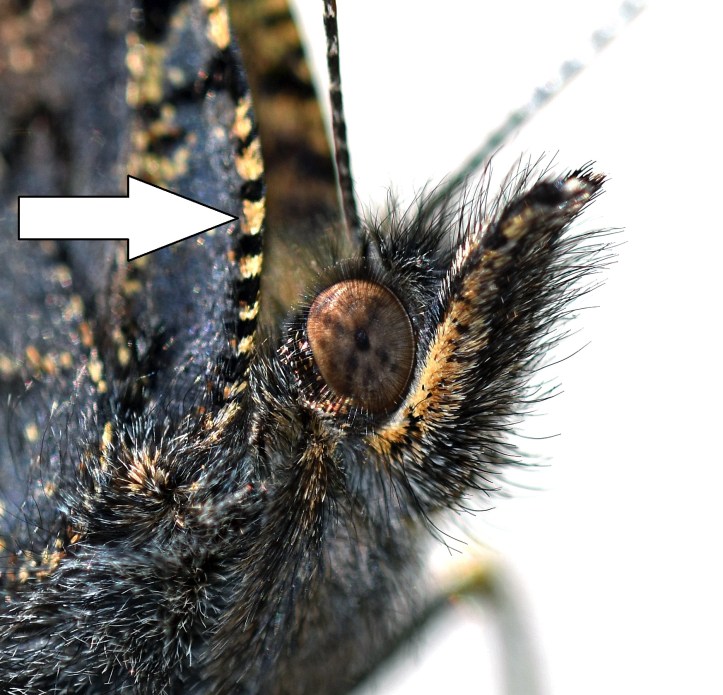

For example, these stripes can be found on the costal region (or leading edge) of the forewings of some butterflies (below). When I went looking through my collection of butterfly photographs, I was surprised to notice how similar some of these marginal patterns are to striped antennae. As shown in this close-up image I took of the front end of a Small Tortoiseshell butterfly (below).

Interestingly, they are often the only parts which are exposed when the insect is at rest. For example, checkered or banded marginal patterns are also visible on the leading edge of Rock Grayling butterflies (below), but in this species the antennae are not very stripy! So what is going on?!

Cott (1940) suggested that these marginal patterns can also be seen on the wings of the Painted Lady, the Grayling, and the Speckled Wood butterflies, but they are sometimes difficult to discern. Nevertheless, a banded marginal pattern is clearly visible on the leading edge of the Painted Lady shown below. Is there any function to these patterns?

There are also very distinctive patterns of a slightly different sort on the leading edges of the forewings of Peacock butterflies (see below). However, in this species, the antennae are also not very striped! So, it is all very confusing!

The distinctive marginal patterns are also very clear in the next photograph of a Peacock butterfly. But what are they for?

Warning patterns

Aposematic (warning) patterns, often consist of high-contrast repetitive stripes, although colours appear to be more important than patterns to birds when learning to avoid dangerous or distasteful prey (reviewed by Stevens & Ruxton, 2012). Amongst butterflies, the typical warning colours are black, yellow, red and orange (see here). However, once again, I find it hard to believe that stipy antennae are playing a role in sending out a warning signal, and most highly aposometic butterflies do not seem to have stripes on their antennae (based on a very cursory survey!).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Stripy legs

Some butterflies have stripy legs as well as stripy antennae, like the pretty little Common tit butterfly (Lycaenidae) shown below. This butterfly has thin black and white ‘tails’ which it moves around in a fairly convincing manner (see False heads and fluffy tails!). So, it appears to be capable of sending messages from both ends of its body: but what exactly is it saying?

Peripheral markings

In disruptive colouration, bold contrasting colours on the animal’s periphery break up its outline and can be an effective means of camouflage (Cuthill et al., 2005). Is this why some butterflies (see below) have such contrasting black and white patterns around their colourful wings?

Prey items are usually detected by their body outline, which is extracted by edge-detecting neurons. It has been suggested that disruptive coloration may have evolved because it confuses the edge-detectors in the brains of would-be predators, ‘making computational inferences about prey shape difficult if not impossible’ (Endler, 2006). Might striped antennae add to this effect? I don’t know!

Motion dazzle and the effect of movement

“Patterns of contrasting stripes that purportedly degrade an observer’s ability to judge the speed and direction of moving prey” (Stevens et al., 2011).

Motion dazzle colouration involves the movement of patterns – such as stripes, bands or markings – which makes the perception of the speed and direction of the bearer difficult to follow. However, I find it hard to believe that antennae function in this way, particularly as they are often held still when the butterfly is stationary.

As someone who watches insects quite a lot, usually as I am trying to photograph them, I am often struck by how different they can look whilst in motion, i.e. compared to when stationary. Indeed, some types of body markings, including butterfly wings, may function more efficiently whilst the animal is in motion, be it for camouflage or signalling. I wrote about this regarding the magnificent Raja Brooke’s birdwing: Camouflage – in whose eyes? It occurred to me that the camouflage markings (leaf-like shapes on the wing) worked better against the foliage when the insect was in flight, but it was only an untested thought (see below).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

It is however, certainly the case that there are situations where it may be more difficult to detect a moving organism against some types of backgrounds, including foliage, and some organisms may have evolved to exploit this effect behaviourally (see Stevens & Ruxton, 2019, for examples).

The importance of contrast

Red admiral butterflies often hold their antenna facing up, almost perpendicular to their bodies, so that (intentionally or not) they catch the rays of the sun when it is low in the sky. The antennae certainly appear very prominent in this type of lighting, which I have captured on several occasions (see below). .

Interestingly, there is no sign of patterning, i.e. antennal stripes, when Red admiral butterflies are viewed head-on, from the front (see below; two different butterflies).

Butterflies with slightly stripy antennae

There are, have we have seen, many butterflies without stripy antennae. Additionally, there are also many butterflies, some of which are shown below, which have only faintly striped antennae. The stripiness does vary to some extent, e.g. with age, lighting, camera angle, and so on. The stripe patterns themselves also vary, i.e. the relative proportions of black (or orange) and white on any given segment. With only a small amount of white in some species.

Some butterflies, like this Provençal (Provencal) Fritillary, Melitaea (Mellicta) deione, have only partial stripes, more spotted than stipy.

It is difficult to generalise. Within the same family, or even genus, some species have very stripy antennae, others do not. However, many structures and features have evolved, only to fade out and disappear in ancestral species. Structures also evolve more than once in some lineages.

This blog has been, hopefully (!), an interesting foray into a rather esoteric subject, but it has been a chance to look again at butterfly wings and to think afresh about whether there are any relationships between the patterns on the wing and the antennae. Insect wings are often adorned with stripes or repetitive patterns of various kinds, either along the wing margins (see below) or within the wing , the latter probably being to create false boundary effects. Notice that there are no striped antennae on either of these nymphalid butterflies (below). Or only, very faintly.

As far as I am aware there has been no experimental testing of the possible effects, if any, of striped antennae. For example, whether they influence in any way the survival of butterflies, either in the lab or the wild. However, given that butterflies often get by with great chunks taken out of their bodies, I expect that they would probably manage without an antennae or two!

References

Ando, T., Fujiwara, H., & Kojima, T. (2018). The pivotal role of aristaless in development and evolution of diverse antennal morphologies in moths and butterflies. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 18(1), 1-12.

Barnett, J. B., Redfern, A. S., Bhattacharyya-Dickson, R., Clifton, O., Courty, T., Ho, T., … & Cuthill, I. C. (2017). Stripes for warning and stripes for hiding: spatial frequency and detection distance. Behavioral Ecology, 28(2), 373-381.

Chen, Q. X., Han, Y., & Li, Y. F. (2024). The Ultramorphology and Sexual Dimorphism of Antennae and Sensilla in the Pale Grass Blue, Pseudozizeeria maha (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Insects, 15(9), 698.

Cott, H. B. (1940). Adaptive colouration in animals.

London, UK: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

Cuthill, I. C. (2019). Camouflage. Journal of Zoology, 308(2), 75-92.

Cuthill, I. C., Stevens, M., Sheppard, J., Maddocks, T., Párraga, C. A., & Troscianko, T. S. (2005). Disruptive coloration and background pattern matching. Nature, 434(7029), 72-74.

Cuthill, I. C., & Székely, A. (2009). Coincident disruptive coloration. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1516), 489-496.

Elgar, M. A., Zhang, D., Wang, Q., Wittwer, B., Pham, H. T., Johnson, T. L., … & Coquilleau, M. (2018). Focus: ecology and evolution: insect antennal morphology: the evolution of diverse solutions to odorant perception. The Yale journal of biology and medicine, 91(4), 457.

Endler, J. A. (2006). Disruptive and cryptic coloration. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273(1600), 2425-2426.

Loxdale H. D., Harrigton, R. and Cannon, R. J. C. (2024). Those jazzy striped butterfly antennae: why do some species have them and others don’t? Antenna. March 2024.

Merilaita, S., Scott-Samuel, N. E., & Cuthill, I. C. (2017). How camouflage works. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1724), 20160341.

Olofsson, M., Dimitrova, M., & Wiklund, C. (2013). The white ‘comma’as a distractive mark on the wings of comma butterflies. Animal behaviour, 86(6), 1325-1331.

Schneider D. 1964. Insect antennae. Annual Review of Entomology, 9: 103-122.

Seymoure, B. M., & Aiello, A. (2015). Keeping the band together: evidence for false boundary disruptive coloration in a butterfly. Journal of evolutionary biology, 28(9), 1618-1624.

Stevens, M., & Merilaita, S. (2009). Defining disruptive coloration and distinguishing its functions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1516), 481-488.

Stevens, M., & Ruxton, G. D. (2019). The key role of behaviour in animal camouflage. Biological Reviews, 94(1), 116-134.9

Stevens, M., Searle, W. T. L., Seymour, J. E., Marshall, K. L., & Ruxton, G. D. (2011). Motion dazzle and camouflage as distinct anti-predator defenses. BMC biology, 9, 1-11.

Thayer, G. H. (1909). Concealing-coloration in the animal kingdom: an exposition of the laws of disguise through color and pattern: being a summary of Abbott H. Thayer’s discoveries. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Fascinating post, Ray, I’ll be thinking about this for months!

Your last two images of the damaged butterflies reminded me of a story from back in the early 1970’s. A friend was consulting with the Air Force regarding ways to modify bomber aircraft to make them more resistant to gunfire. My friend was supplied with piles of detailed photos of bullet holes in various parts of aircraft that had returned to base badly damaged. He carefully designed patches that could be applied to the areas most frequently suffering holes, and was about to submit his recommendations, when he was struck by an alarming thought: the photos of aircraft damage had all been taken of aircraft that made it back to base. The places that needed reinforcement were the locations NOT showing damage… because any damage to those locations proved fatal, and the aircraft was lost.

Long winded, sorry… but the moral of the story might be that the butterfly parts needing protection are those we never see significantly damaged on a living speciman.

as noted at the end of the post, predator damage to butterfly parts has been an area of study to try to answer these ‘Why?’ questions. Thank you for this engaging article.

Thank you for a stimulating article. My mother (aged 90) wonders why insects have symmetrical wing patterns, as to humans this makes them easier to pick out from the background. I assume it is so much more efficient genetically to have just the one design, repeated. Or could it be that other predators are less aware of symmetrical objects than we are?

Very interesting Ray and some fabulous photos. I wonder if the answer is in part in Sam Rappen’s fascinating response that, the antennae are crucial and there is a selective advantage in disguising limbs and antennae while the brilliant, easily seen wings can take a bit of life’s flak without necessarily endangering the often short life before the adult has done its crucial time-limited business. But as always fascinating stuff and more people shd read it.

Another fantastic article Ray, and as ever beautifully illustrated.