It’s a long way from Iceland to the Antarctic, but Arctic terns fly there and back, every year! Strange to say, I had only seen Arctic terns in the Antarctic, before I went to Iceland. I saw some on their wintering grounds – which is typically along the edges of the pack ice – as we were approaching the South Orkney Islands, in Antarctica. That was back in 1982!

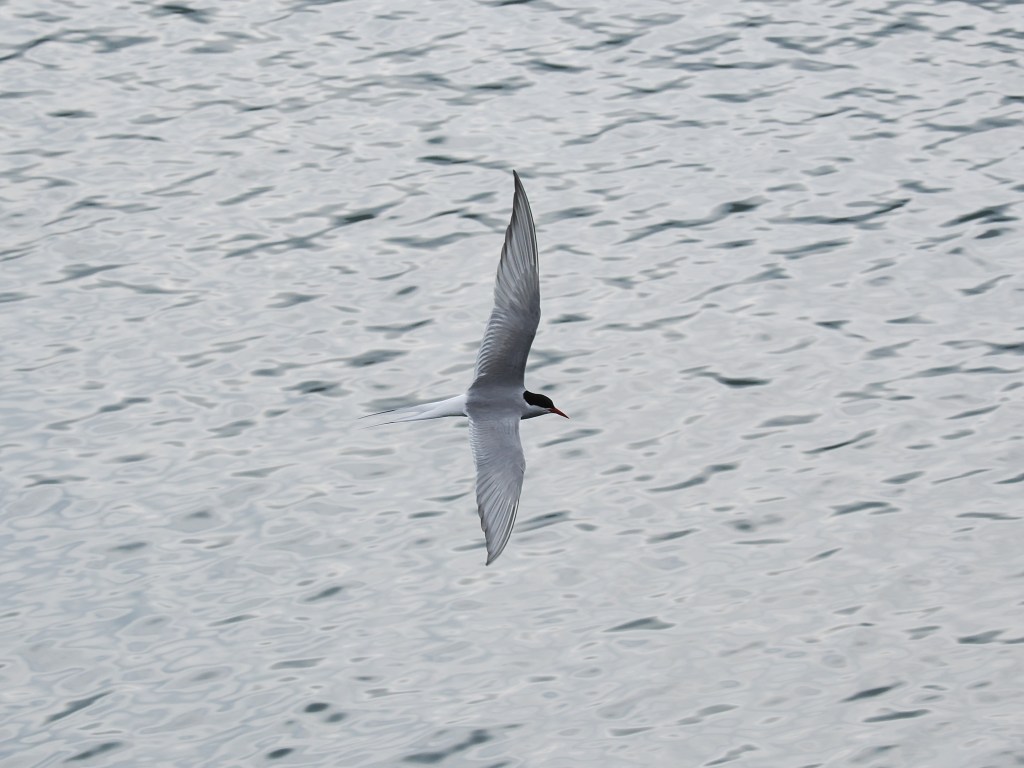

This year, I was fortunate enough to go on a trip to Iceland, where I saw masses of Arctic terns. A really beautiful bird, and although there are over 250,000 breeding pairs in Iceland (20-30% of the worldwide population), their numbers are declining. However, I saw Arctic terns wherever we went in Iceland, first of all at small port of Grundarfjörður, where the terns were nesting on the beach and fishing in the harbour.

One bird stopped for a rest on some railings next to the harbour and did not seem to mind me creeping up to photograph him/her!

Arctic terns are fantastically good at fishing, spotting a small fish as they fly over the water, then turning and diving to scoop it up! I don’t know how long it takes them to learn this behaviour; I expect they learn how to do it very quickly by watching their parents and perfecting their technique.

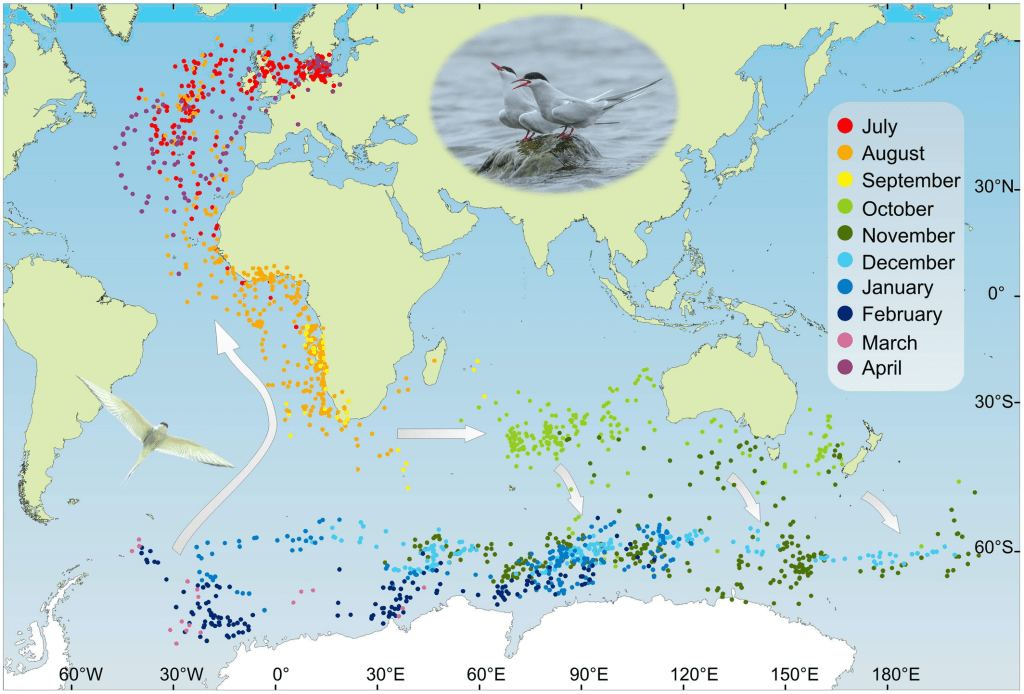

It’s a long way from Iceland to the Antarctic, and Arctic terns typically make annual direct round-trip of perhaps 40,000 kilometers (not including daily foraging flights)! They spend about a third of their annual cycle was amongst Antarctic sea ice.

We now know, thanks to a host of recent studies attaching miniature geolocators to Arctic terns, that some individuals actually travel more than 80,000 km annually! Over a lifetime of 30 years or more, that adds up to well over two million miles. That is extraordinary!

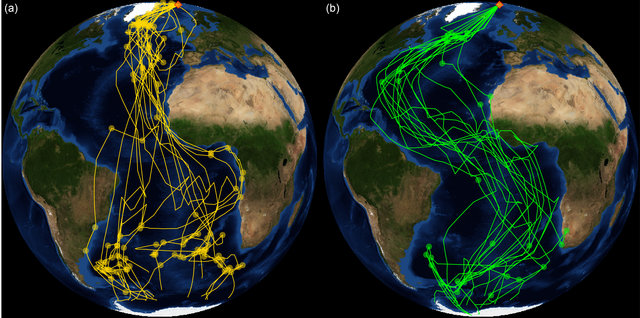

Carsten Egevang and colleagues (2010) attached miniature ‘archival light loggers‘ (weighing 1.4 g) to plastic leg rings on breeding Arctic terns in Greenland and Iceland. See here for more details. They found that individual birds followed two different migration routes south: some followed the coast of West Africa, whilst others crossed the Atlantic just north of the Equator and then went south along the South American continent.

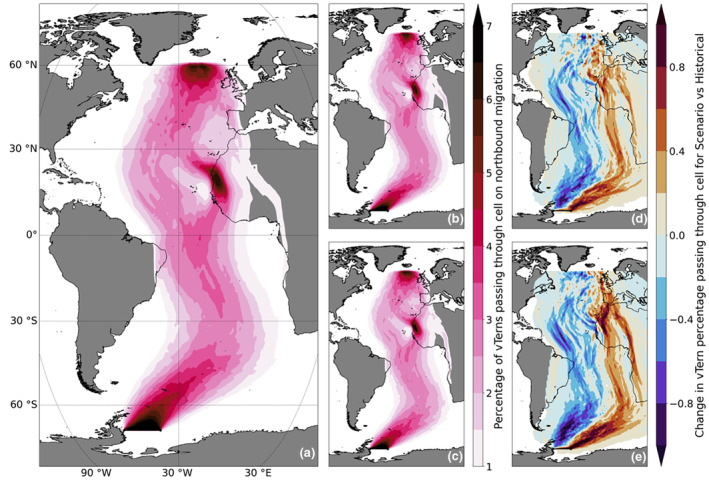

On the return journey in spring, the northbound migration is more than twice as fast and the birds follow an “S” shaped pattern through the Atlantic Ocean. This is also illustrated in the study by Morten et al., 2023 (see below).

Altogether, the Arctic tern experiences more sunlight in a calendar year than any other creature on Earth. They breed in the far north (in the northern hemisphere) where summer days are long, and then spend about four months in the far south (in the southern hemisphere) feeding on krill (Euphausia species), when the days are at their longest, from November to February.

In the south and west of Iceland, terns and other seabirds rely mainly on sand eels, but in the cooler waters off north and east Iceland, they feed on capelin and krill (Morten et al., 2022).

Recent population declines of arctic terns are due to poor survival of juveniles. Arctic terns also lay smaller clutches if food quality is poor during courtship feeding. The collapse of sand eels (Ammodytes sp.) in Icelandic waters, most probably as a result of warming seas caused by climate change, has coincided with lower adult survival rates, and low fledgling rates caused by starvation.

The juveniles terns I saw along the seashore at Grundarfjörður (on the Snæfellsnes peninsula in the west of Iceland) however, seemed to be receiving plenty of sand eels from their parents, at least during the short time I was there photographing them.

Arctic terns generally fly at low levels whilst searching for food but can soar up to over 1,000m altitude if they need to. They have short foraging ranges and generally stay within 10 km of the colony; usually, much less, as foraging trips during the breeding season are short and the terns only carry only one, or a few prey items at a time. Not like puffins, which can hold dozens of small sand eels (the record is 83!) in their beaks.

Arctic terns have a sequence of courtship rituals, beginning shortly after they arrive back at their breeding grounds. Courtship involves attraction, evaluation and persuasion. There are usually elements of display – typically by the males – and assessment – typically by the females; although these roles are reversed in some species: for example, in red phalaropes, it is the females who perform courtship displays and actively seek out a mate, and the males incubate the eggs and nurture the young.

In Arctic terns however, both males and females incubate the eggs, taking turns to keep them warm for the ca. 21-23-day incubation period, and both parents also work together to feed and care for the young birds after they hatch.

I didn’t manage to see a ‘high flight’, where the female chases a male high into the air, and they then slowly back down to the ground. However, I did witness quite a few ‘fish flights’ above a colony, right next to where the ship was docked in Akureyri, a town in northern Iceland.

The male carries a small fish – usually a sand eel – in his bill and flies low over the colony to attract the attention of a female. An interested female will follow the male as he descends.

The female may initially beg for the fish before the male finally presents it to her. I guess she’s evaluating how good a provider he will be! I took a number of shots of Arctic terns on a breeding site where there were many chicks sitting in the grass, waiting for their parents to deliver them a fish supper!

On the ground, males display using a very distinctive posture, with the male tilting his head down and holding his wings down and out from the body, while the female stands nearby with her head pointed upwards.

The male strutting and bowing in front of the female is showing himself off, and if the female is sufficiently impressed she becomes receptive, she will solicit food from him.

After an initial, successful fish exchange, the male will continue to feed the female in the days leading up to egg-laying, which helps solidify their pair bond. The pair bonds of Arctic terns are strong and enduring, and are usually reestablished every year even though they appear to migrate separately and even overwinter at different locations (see Redfern, 2021).

After mating, females lay one to three eggs, though a clutch of two is most common. Both parents take turns incubating the eggs (for about three weeks), and after the chicks hatch, both parents share the task of brooding and feeding them with small fish. I took a number of shots of relatively young chicks, on a rocky site away from the larger grassy one.

Chicks can move around within a few days of hatching, but usually stay near the nest and rely on their parents for food for about 21-24 days or so, before fledging. They can even swim, if they need to, at two days old; when they are just fluff balls!

They start flying about 21-28 days after hatching, but continue to be fed by their parents for another month or two, before the family begin their migration south toward Antarctica together. The juveniles stay with their parents until they are fully capable of feeding themselves and navigating independently.

The young (first year) birds do not breed in the following summer, and I think I am right in saying that they do not migrate north again for a few years. Thus, they spend their first few years in the southern hemisphere before somehow, returning to their original breeding grounds to reproduce when they are between two to four years old.

They truly are astonishing!

Links

https://www.carstenegevang.com/single-post/the-arctic-tern-extreme-migration-from-pole-to-pole

https://www.carstenegevang.com/arctictern

References

Alerstam, T., Bäckman, J., Grönroos, J., Olofsson, P., & Strandberg, R. (2019). Hypotheses and tracking results about the longest migration: The case of the arctic tern. Ecology and Evolution, 9(17), 9511-9531.

Egevang, C., Stenhouse, I. J., Phillips, R. A., Petersen, A., Fox, J. W., & Silk, J. R. (2010). Tracking of Arctic terns Sterna paradisaea reveals longest animal migration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(5), 2078-2081.

Hromádková, T., Pavel, V., Flousek, J., & Briedis, M. (2020). Seasonally specific responses to wind patterns and ocean productivity facilitate the longest animal migration on Earth. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 638, 1-12.

Morten, J. M., Burgos, J. M., Collins, L., Maxwell, S. M., Morin, E. J., Parr, N., … & Hawkes, L. A. (2022). Foraging behaviours of breeding arctic terns Sterna paradisaea and the impact of local weather and fisheries. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8, 760670.

Redfern, C. P. (2021). Pair bonds during the annual cycle of a long-distance migrant, the Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea). Avian Research, 12(1), 32.

Redfern, C. P., & Bevan, R. M. (2020). Use of sea ice by arctic terns Sterna paradisaea in Antarctica and impacts of climate change. Journal of Avian Biology, 51(2).

Volkov, A. E., Loonen, M. J. J. E., Volkova, E. V., and Denisov, D. A. (2017). New data for Arctic terns (Sterna paradisaea) migration from White Sea (Onega Peninsula). Ornithologia 41, 58–68

As you say amazing birds and great images!