Dragonflies probably have the best vision in the insect world. Their large compound eyes are made up of up to 30,000 facets (or ommatidia), arranged in different zones, and with many more photoreceptor types than us humans! They also have near 360°, wrap-around vision, and sensitivity across a broad spectral range, from UV to red. So, they see the world in ‘ultra-multicolour‘, or at least we think so!

Here, I look how different regions of dragonfly compound eyes are used for activities such as catching fast-moving prey and for detecting polarised light (put on your sun glasses for that!).

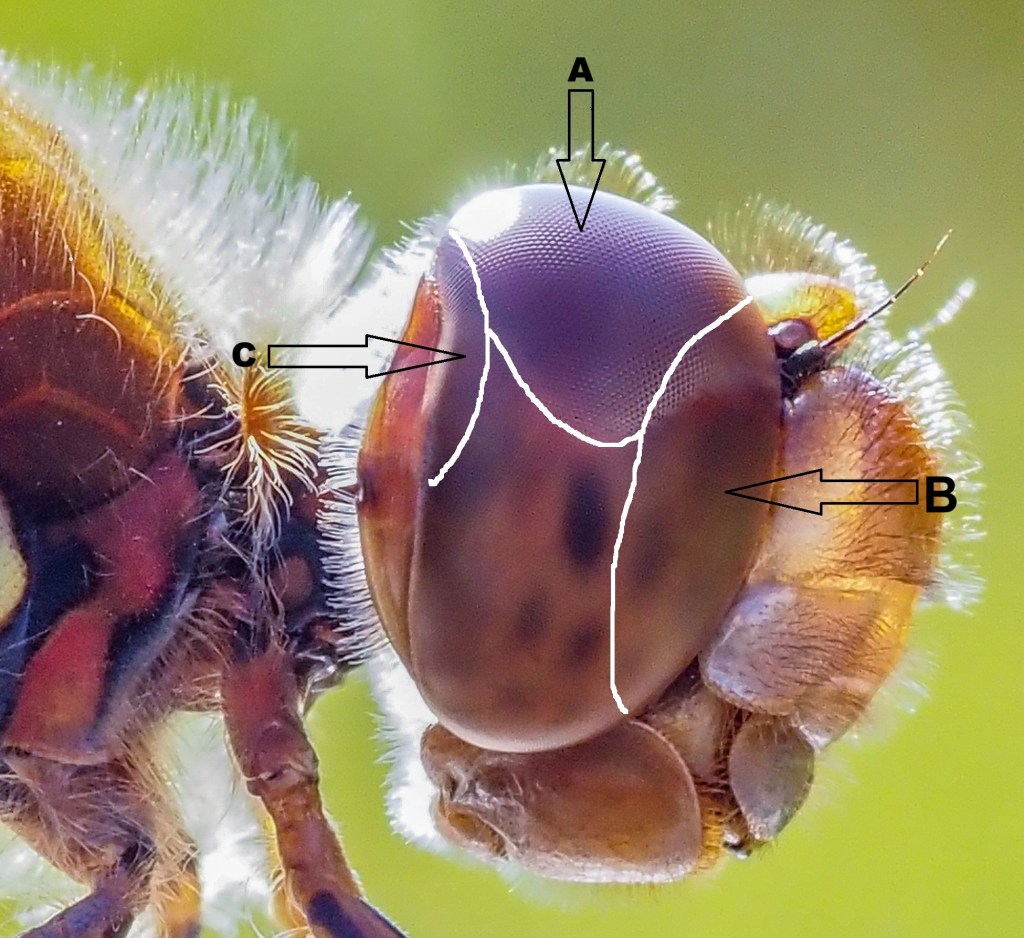

Dragonflies, such as the Common darter, Sympetrum striolatum (below) for example, have large compound eyes clearly divided into upper (dorsal) and lower (ventral) regions. A feature seen in many different species: see previous blog on dragonfly eyes.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Zones or specialised areas of the eye

The different regions of dragonfly eyes are adapted for different behavioural tasks. The upper (dorsal) sector has pale yellow-orange screening pigments and extremely large facets, which can be seen in the above photo. A zone of high-resolution, called the dorsal acute zone, is located on the upper part of the dragonfly’s compound eyes (see below, A). It provides exceptional visual acuity and is used for detecting and tracking prey (or other dragonflies) flying above the predator, against the background of a bright sky.

The upper part of the dorsal region also contains a pronounced fovea – a region that provides the greater visual acuity – where there are larger ommatidia that are arranged almost parallel to each other. If I understand the biology correctly, the shape and position of the largest pseudopupil indicates the location of the dragonfly’s fovea (see below), i.e. the area of greatest visual acuity. (However, the position of the pseudopupils shift with the angle of observation). The other smaller dark spots are secondary pseudopupils.

The largest and darkest spot – the principal pseudopupil – is that part of the compound eye which is facing directly towards the camera. These pseudopupils are not fixed, but move with the angle of view of the observer, or lens, as explained here in a blog I did about about butterfly eyes. The pseudopupil is located in the lower sector of the compound eye in this picture (below) I took of a perching female Scarlet Grenadier (Lathrecista asiatica) in Thailand.

With the primary black spot (or pseudopupil) on an insect’s compound eye, one is, in effect, looking right down into a small group of ommatidia – down their vertical axis – and little or no light is scattered back out again, because of black screening pigments. It is explained in a very detailed paper (far too complicated for me!) by Professor D. G. Stavenga (1979).

The frontal acute zone is shown in the picture of the Common darter (Sympetrum striolatum) above, with zones marked (by the left-pointing arrow in the image, B). N.B. I have drawn these zones on one of my own photographs, based on an illustration in a paper by Lancer et al. (2020), see here, which is not in the public domain (i.e. is under copyright).

In another research paper, by Rigosi et al. (2021) a broad frontal acute zone is shown for the southern hawker (Aeshna cyanea) and occupies a large area of the frontal part of the eye, see here. The frontal acute zone is a region with a high density of ommatidia, facing the front of the insect, and is the part of the eye which the insect uses to fixate on items of interest, like flying prey.

Perchers: sit-and-wait predators.

Perching dragonflies usually choose sites where they they can scan a large area while basking, and from which they can swiftly take off and pursue prey, or other dragonflies that invade their territory (see below).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Dragonflies are highly effective aerial predators, swooping upwards from beneath their flying prey and grabbing it with outstretched legs. I once watched a dragonfly catch a butterfly in this way. It flew up to the top of a tree and bit off the wings of the butterfly, which floated gently down to the ground as the odonate tucked into the body of the hapless victim.

There is a high frequency of head-cocking in perched dragonflies. Head-cocking behaviour typically involves rapid saccadic movements: either rolling the head from side-to-side (below) or moving it up-and-down in the pitching plane. There can also be a yawing motion, which is probably a form of visual tracking.

N.B. a saccade is a quick, simultaneous movement of both eyes between two or more phases of fixation in the same direction (Wikipedia).

It is the phenomenon of motion parallax, which is probably elicited by such head movements, providing information to the dragonfly about the prey distance, before take-offs (Olberg et al., 2000).

“The form of the eye in many insects strongly suggests that they measure range over long distances by parallax rather than by binocular overlap.” (Horridge, 1977)

Remarkably, when pursuing a prey item, dragonflies fly towards a point in front of the target, cleverly intercepting it by predicting the flight path (Olberg et al., 2000). In other words, they don’t just chase after something they want to catch; they calculate where it is going to be in a few microseconds time, and fly straight towards the point of intersection!

The dragonfly computes an interception flight trajectory and steers to maintain it during its prey-pursuit flight. In cocking its head therefore, a perching dragonfly is trying to discriminate the target and calculate its distance from where it is sitting. It is trying to get a fix on the target by aiming the forward-looking zones of the eyes towards the target.

Libellulid dragonflies track potential prey items by making smooth head movements (Lin and Leonardo, 2017) which keeps the prey image centred on the fovea (Olberg et al., 2007), and provides the predator with the best possible image to use whilst deciding whether to launch an attack.

Damselflies also do these head cocking movements (below right).

13 June 21

When prey items fly near a perched dragonfly, they trigger a very rapid, 50 millisecond (ms) head movement, or saccade, that fixes the object in the dragonfly’s visual fovea (see above), where the resolution of the compound eye is at its greatest. Smooth head tracking movements by the dragonfly continue to hold the prey image steady on the dragonfly’s fovea for another 250 ms.

Flight is triggered as the prey passes directly above the dragonfly, but each interception only lasts for a very brief 300-600 ms, i.e. less than a second (Lin et al., 2024). The dragonfly computes whether or not to pursue the prey in this brief period of time.

As clearly visible in the photograph shown above, the ommatidial facets are larger in the dorsal region of the compound eye – dominated by blue and UV photoreceptors – compared to the rest of the eye, and are well-adapted for spotting flying insects against the background of a blue sky.

“Larger facets allow greater resolution for individual ommatidia of the eye; smaller angles between their axes allow a greater density of sampling stations.” (Horridge, 1977)

In flight

Whilst actively chasing prey items, dragonflies adjust the orientation of their heads in order to maintain the image centred on a virtual crosshair, formed by the ‘visual midline and the dorsal fovea’, a band of high visual acuity that crosses the midline of the eye (Oldberg et al., 2007).

Potential prey items flying through the sky in the visual field of a dragonfly usually only occupy a very small zone, rarely more than 1° of visual space, and these tiny targets stimulate only two or three ommatidia of the compound eye (Lancer et al., 2020). That’s a minute proportion of the total number of facets in the eye. Furthermore, these potential targets are often observed against a mass of other flying insects, both possible prey items, like flies or mayflies, as well as other dragonflies and damselflies in the area. So there is a lot going on in the brains of damselflies and dragonflies as well as in the eyes, to sort out all these tiny fast moving targets to discern what they are, and decide whether they are worth chasing.

Polarised light

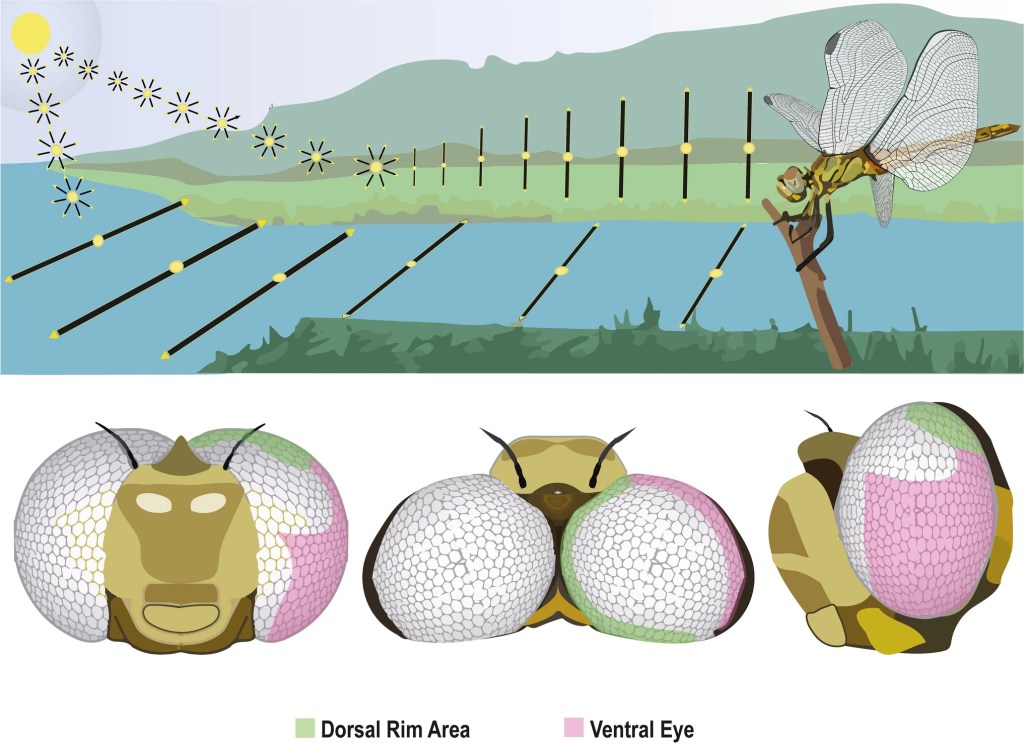

Dragonflies can detect the plane of polarisation of light; something which we humans need sunglasses to do! When dragonflies are perched near water bodies – where they gather to find mates or lay eggs in the case of the female – the upward-facing dorsal rim area of their eyes (green areas in figure below) detects skylight polarization patterns. Similarly, the downward-facing polarization-sensitive cells detect polarised light reflected from water or the ground.

The dorsal rim area (see above) is a narrow band of specialised ommatidia along the dorsal edge of the eyes, containing polarisation sensitive photoreceptors.

References

Cezário, R. R., Lopez, V. M., Datto-Liberato, F., Bybee, S. M., Gorb, S., & Guillermo-Ferreira, R. (2025). Polarized vision in the eyes of the most effective predators: dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata). The Science of Nature, 112(1), 8.

Gonzalez-Bellido, P. T., Talley, J., & Buschbeck, E. K. (2022). Evolution of visual system specialization in predatory arthropods. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 52, 100914.

Horridge, G. A. (1977). Insects which turn and look. Endeavour, 1(1), 7-17.

Labhart, T., & Nilsson, D. E. (1995). The dorsal eye of the dragonfly Sympetrum: specializations for prey detection against the blue sky. Journal of comparative physiology A, 176, 437-453.

Lancer, B. H., Evans, B. J. E., & Wiederman, S. D. (2020). The visual neuroecology of anisoptera. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 42, 14–22.

Lin, H. T., & Leonardo, A. (2017). Heuristic rules underlying dragonfly prey selection and interception. Current Biology, 27(8), 1124-1137.

Lin, H. T., Siwanowicz, I., & Leonardo, A. (2024). Wireless recordings from dragonfly target detecting neurons during prey interception flight. bioRxiv, 2024-11.

Miller, P. L. (1995). Visually controlled head movements in perched anisopteran dragonflies. Odonatologica, 24(3), 301-310.

Olberg, R. M. (2012). Visual control of prey-capture flight in dragonflies. Current opinion in neurobiology, 22(2), 267-271.

Olberg, R. M., Worthington, A. H., & Venator, K. R. (2000). Prey pursuit and interception in dragonflies. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 186, 155-162.

Olberg, R. M., Seaman, R. C., Coats, M. I., & Henry, A. F. (2007). Eye movements and target fixation during dragonfly prey-interception flights. Journal of comparative physiology A, 193, 685-693.

Rigosi, E., Warrant, E. J., & O’Carroll, D. C. (2021). A new, fluorescence-based method for visualizing the pseudopupil and assessing optical acuity in the dark compound eyes of honeybees and other insects. Scientific reports, 11(1), 21267.

Sauseng, M. A., Pabst, M. A., & Kral, K. (2003). The dragonfly Libellula quadrimaculata (Odonata: Libellulidae) makes optimal use of the dorsal fovea of the compound eyes during perching. European Journal of Entomology, 100(4), 475-480.

Stavenga, D. G. (1979). Pseudopupils of compound eyes. In Comparative physiology and evolution of vision in invertebrates (pp. 357-439). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

I’ve always been fascinated by the different strategies animals use to receive optical signals. Compound eyes are such incredibly complex organs. It’s hard to imagine how the tiny brain of a dragonfly is able to process all the incoming signals in the twinkling of an eye (pun intended 😉), isn’t it?

Yes it is! However, scientists studying Drosophila seem to be making good progress in understanding some of the mechanisms and nerve cells inolved in the optic lobes and the tiny (200,000 neurons?), but perfectly adequate, brain! About 100 billion neurons in ours, and 100 trillion synaptic connections, I think!😁

I find your article about vision in dragonflies very informative. Particularly noteworthy is the hunting behaviour, in which the dragonflies cut off the flight path of the prey. The investigation of the underlying neuronal mechanism is a challenge. By the way, my correct name is Karl Kral; see literature citation Sauseng et al. (Kral K.)

Best wishes,

Karl

Many thanks Karl, nice to meet you. Google Scholar does that to references! I’ve corrected it. I dive into the literature to accompany my photographs, and for my own education as there is always so much to learn, especially from studies like yours😁