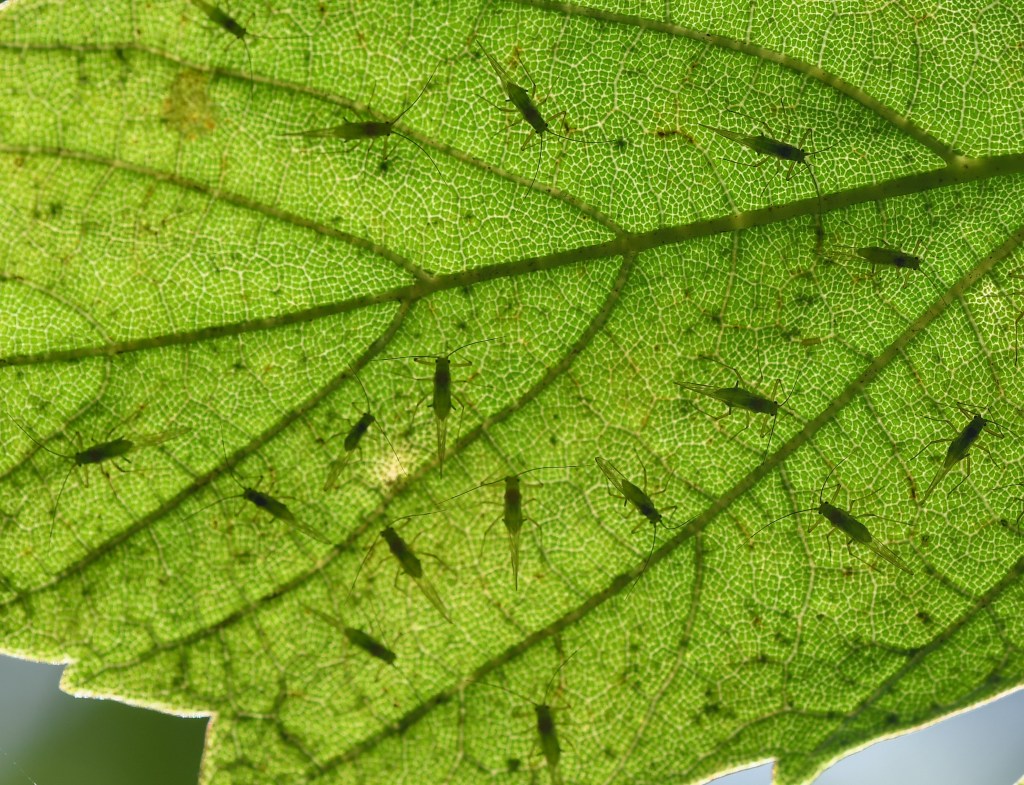

One day in late April this year, I chanced upon some newly opened sycamore buds with fresh leaves, no more than a few days old. The low afternoon light backlit the leaves and highlighted the aphids which were crowding onto the undersides (below).

At least eight species of aphids can be found on sycamore trees in the UK (see here) but probably the most common is Drepanosiphum platanoidis (= platanoides), appropriately called the Common sycamore aphid. The species is autoecious, which means that it completes its entire life-cycle on sycamore trees. However, it readily colonises other types of sycamore trees, albeit on a more casual basis.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

There are fabulous photos of the common sycamore aphid (and many other species) on this site by Bob Dransfield and Bob Brightwell.

Sycamore aphids are found on the undersides of leaves, so when you go looking for them, remember to keep turning over the leaves. It is usually more sheltered on the underside of a leaf and probably easier to access the phloem sap which aphids feed on. Rumour has it there are also more stomata there, which makes access to the phloem easier for the aphids.

Common sycamore aphids, Drepanosiphum platanoidis Schrank, lay their eggs in the autumn on rough, or creviced bark of sycamore trees, Acer pseudoplatanus L., some distance (>50 cm) from the buds (Dixon, 1976; Wade and Leather, 2002). Here are some sycamore aphids waiting for the buds to open (below).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

So, when the first instar nymphs hatch out in spring, they have quite a long way to crawl in order to access some food, especially for insects so small!

Freshly laid eggs of D. platanoidis are pale yellow to green coloured when they are first laid, in the autumn, but soon darken to shiny black. Large numbers of eggs die over winter, with mortality rates up to 79% recorded on sycamore tree trunks in the study by Wade and Leather (2002), carried out in Silwood Park, Berkshire.

“The advantage to aphids of hatching at bud burst is that in feeding on the unfurling leaves aphids can achieve twice the adult weight and their offspring can mature more quickly and achieve a greater size than aphids that emerge after bud burst” (Dixon, 1976).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

So, as leaves of sycamore are unfurling the phloem sap is a very rich food for sycamore aphids. No wonder they crowd together so densely on the fresh leaves!

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

To reiterate, aphids which are able to move onto the leaves at budburst can reach twice the adult weight – relative to those that don’t make it onto the crowded new leaves – and can thus maintain a higher reproductive rate (Dixon 1970, 1975). In other words, it’s a scramble to get onto the fast-growing, nutrient rich young leaves.

Aphid biology has some funky terms, presumably invented by zoologists who had a classical education and were fluent in Latin! For example, in spring, when the sycamore buds begin to develop, the eggs hatch, and the nymphs develop into winged parthenogenetic adults called fundatrices, or more prosaically, stem mothers. The singular term, fundatrix, essentially means ‘foundress’, so in this case, it refers to a female aphid that establishes a new colony; the first of the year.

These adults then give rise to more nymphs called fundatrigeniae – viviparous parthenogenetic wingless female aphids produced by a fundatrix – and these in turn give rise to further wingless forms which develop into parthenogenetic virginoparae. Fancy names for three generations of female aphids produced by asexual reproduction. Sex comes later in the year!

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Two parthenogenetic generations then occur in succession until the onset of autumn when nymphs are produced that develop into apterous (i.e., wingless) egg-laying females and alate (winged) males. These sexual morphs mate and the oviparae lay the overwintering eggs (Dixon, 1973).

For more on aphid life cycles, see this blog by Simon Leather here (Aphid life cycles – bizaare, complex or what?).

Returning to the life-cycle of the Sycamore aphid, adults of Drepanosiphum platanoides undergo a reproductive diapause during the summer, which means that there is a virtual absence of nymphs during June and July, when the plant effectively stops growing (Dixon, 1963). This is when the aphids spread themselves out over the whole surface of the mature sycamore leaf, in contact clustered distributions: something I described in a previous blog (Spaced out aphids!). They adopt this highly organised separation because feeding aphids kick out at other individuals who come too close to them; they like to maintain their own little feeding (sucking!) patches!

The aphids that develop from the overwintering eggs in spring (the fundatrices) are always green often with bold black transverse bars on the abdomen. The offspring of fundatrices, which reach maturity in summer, are always very pale with no black bars and with paired white wax patches on the abdominal segments. They are also usually green (see below).

Bud burst

Surprisingly, egg hatch is not particularly closely synchronized with bud burst on any particular tree (Dixon, 1976). Variations in the seasonal timing of egg hatch from year to year are related to differences in temperatures between years, but the aphid and its host do not respond to ambient temperatures in the same way.

Analysis of a long-term dataset, collected by the late Professor Simon Leather, at the Imperial College field station at Silwood Park (from 1993 to 2012), showed that the dates at which sycamore budburst occurred, varied by up to 17 days, across this 20-year period (Senior et al., 2020).

Simon Leather described this ‘mega-project’ in one of his blogs:

“Once a week for twenty years, me and on some occasions, an undergraduate research intern, walked along three transects of 52 sycamore trees, recording everything that we could see and count and record, aphids, other herbivores, natural enemies and tree data, including leaf size, phenology, height, fruiting success and sex expression.” (Leather, 7 May 2019).

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

The insect components of this system, i.e. the aphids and their parasitoids, displayed even more variability in their phenology than the trees themselves.

Drepanosiphum platanoidis emergence dates varied by a massive 76 days – that’s a difference of about two and a half months! – over the course of the 20-year study period. However, somewhat surprisingly (to me, at least), the mismatches in timings between aphid emergence and budburst did not adversely affect the population growth rate of the aphid. Somehow, they managed to catch up, and even-out, the lack of synchrony between tree and insect.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

The dataset collected by Simon Leather was long enough (the benefits of long-term data sets are not always appreciated by funding bodies) to assess the effects of climate change on the phenology of budburst over the period. Analysis revealed that sycamore budburst at this site in southern England advanced by approximately five days, in association with the approx. 1 deg C increase in March and April temperatures that occurred between 1992 and 2012 (Senior et al., 2020).

Budburst dates are correlated with warmer temperatures during the late winter and early spring, being earlier when spring is warmer. In contrast, warmer temperatures in late winter delayed the emergence of sycamore aphid species, but interestingly, their population growth rates were not adversely affected by this mismatch with their host plant.

“[Sycamore] aphid population growth rates appear to currently be resilient to delayed emergence relative to sycamore bud burst.” (Senior et al., 2020).

The world is getting warmer, the spring is coming sooner, and the aphids have to cope with these climatic changes. The good news – if you like aphids, that is, and they are vital components of the forest ecosystem! – is that is that this species, at least, seems to be capable of adapting to the changes we are inflicting on nature.

There is much that could be said about aphid phenology, but I’ll finish by saying that the sycamore aphids I photographed here seem to me to have timed their hatching remarkably well. They managed to climb aboard their tasty, nutrient-providing buds just as they were bursting open! Enabling them to build up their colonies just as the trees were waking up and starting to grow again, pumping nutrients into the developing leaves. Long may they continue to do so.

I revisited the same tree two weeks later, to check on the progress of the aphids! They were still there, on the more mature leaves (see below), but there seemed to be many more smaller nymphs: the next generation I would guess. I.e fundatrigeniae!

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

References

Abernethy, R., Garforth, J., Hemming, D., Kendon, M., Mc-Carthy, M., & Sparks, T. (2017). State of the UK Climate 2016: Phenology supplement. 39 pp.

Dixon, A. F. G. (1963). Reproductive Activity of the Sycamore Aphid, Drepanosiphum platanoides (Schr.) (Hemiptera, Aphididae). Journal of Animal Ecology, 32(1), 33–48.

AFG Dixon, A. D. (1970). Quality and availability of food for a sycamore aphid population. al Populations in Relation to their Food Resources (Ed. by A. Watson), pp. 271-87. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford.

Dixon, A. F. G. (1975). Effect of population density and food quality on autumnal reproductive activity in the sycamore aphid, Drepanosiphum platanoides (Schr.). The Journal of Animal Ecology, 297-304.

Dixon, A. F. G. (1976). Timing of egg hatch and viability of the sycamore aphid, Drepanosiphum platanoidis (Schr.), at bud burst of sycamore, Acer pseudoplatanus L. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 593-603.

Senior, V. L., Evans, L. C., Leather, S. R., Oliver, T. H., & Evans, K. L. (2020). Phenological responses in a sycamore–aphid–parasitoid system and consequences for aphid population dynamics: A 20 year case study. Global change biology, 26(5), 2814-2828.

Wade, F. A., & Leather, S. R. (2002). Overwintering of the sycamore aphid, Drepanosiphum platanoidis. Entomologia experimentalis et applicata, 104(2‐3), 241-253.

Links to blogs by Professor Simon Leather

https://simonleather.wordpress.com/tag/drepanosiphum-platanoidis/

https://simonleather.wordpress.com/tag/drepanosiphum-platanoidis/

https://simonleather.wordpress.com/2019/05/07/satiable-curiosity-side-projects-are-they-worthwhile/

[…] Two species commonly occur on the undersides of sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) leaves: the Common Sycamore Aphid (Drepanosiphum platanoidis); and the Sycamore periphyllus aphid (Periphyllus acericola); there may be other species of well (see here). Drepanosiphum platanoidis is probably the most common aphid on sycamore and readily colonises new leaves in the spring (below) when the phloem sap is flooding into the unfurling leaves (See previous blog: Sycamore aphids on buds and new leaves). […]