There are many things in this marvelous world of ours that we sometimes take for granted. One of them, I think, is the miraculous appearance of new leaves each year on temperate trees.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Aliens, might arrive here on planet Earth and be amazed at the regenerative ability of plants: Their plasticity, and capacity to regrow, reform, replenish and recycle themselves.

We might say: “Yes that’s what plants do; tiny buds appear each year on gnarly old branches, then leaves emerge and grow, capture sunlight, fix carbon, produce oxygen, and fall off again!”

They might reply; “Do you know how amazing that is?! We have travelled the universe and have never come across living things with such an ability to renew themselves, and to continuously replace all of their aging parts, quite so effectively as these organisms!”

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Of course, we all marvel at the reappearance of leaves each year. Their emergence from buds every spring is something wonderous, but how much do we know about the process? This year, I thought I would dig a little deeper into the subject, to try and educate myself a little about how trees go about their annual reclothing; or re-leafing; is there a better word to describe it? Regreening?

Somehow, trees retain the ability to produce new leaves and new flowers throughout their long lives. How do they do it? Where does this regrowth begin? What and where are the basic building blocks, the primordial cells, that enable them to do this?

The growth and development of plant leaves follow an ancient program that is flexible and adaptable and has been modified over aeons of time into countless varieties, or variations, expressed in the magnificent biodiversity of trees we see in our precious flora.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Stem cells

Leaves start life in specialised ‘proliferative’ tissues called meristems, which occur on the tips of roots and shoots. These growing points contain actively dividing cells which continuously generate new tissues for the plant.

Meristems contain a special, highly regulated microenvironment called a stem-cell niche (SCN) that provides the chemical signals and physical support needed to maintain the pluripotent stem cells. In other words, these special cells have the remarkable ability to differentiate into all of the cell types found in the plant, and this property lasts for the duration of the trees life; hundreds of years in many cases.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Continuous differentiation

A small population of stem cells at the heart of the meristem constantly renews itself, slowly dividing throughout the life of the tree, giving rise to daughter cells that can either differentiate to form new tissues and organs, or remain undifferentiated, as stem cells.

It is this property which is so special. Animal stem cells, especially in adult organisms, have a fairly limited ability to differentiate into different cell types, whereas plant stem cells, sitting in the heart of the meristem, can change themselves into any of the plant cell types in the plant, and this miraculous superpower lasts throughout the plant’s life.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Plants are special

Of course, we all start life from a small number of embryonic stem cells in the early embryo (the blastocyst), but they don’t last long in the pluripotent state. Their ability to create the 200 or so different types of cells in the human body, for example, only lasts for about seven days. Stem cells remain in adults – for example in bone marrow, where they make blood cells – but they can only differentiate into the cells that grow in that region, i.e. within a specific tissue type.

So, animal stem cells have a limited potency in post-embryonic stages and are mainly involved in tissue repair, regeneration, and the maintenance of specific cell types. Plant stem cells, on the other hand, remain pluripotent within meristems, and can differentiate into any plant cell type, including those that form leaves, stems, and roots. This property, let’s call it a superpower, to be able to differentiate throughout their life, is what so impressed my fictional aliens!

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Leaf formation

Unlike stems and roots, which can, in theory, carry on growing throughout the life of the plant – i.e. as a result of the uninterrupted supply of cells from the meristems – plant leaves do not have a self-renewing meristem and thus, cannot grow indefinitely. They fall off and die!

Plant cells can go down one of two pathways of differentiation: terminal and non-terminal. Those on the terminal path can no longer change their fate, once fixed; while those on non-terminal pathways retain an ability to change their destinies when exposed to certain signals, events or changes.

In other words, some plant cells retain their stem cell potential. This is why we can hack plants about, repot them, replant them, trim them, and even cut them down, and they still grow back! Another extraordinary feature we often take for granted.

Even more remarkably, any plant cells can, in theory, de-differentiate and return to a pluripotent state, e.g. after wounding; whereas in animals this capacity is limited to embryonic stem cells.

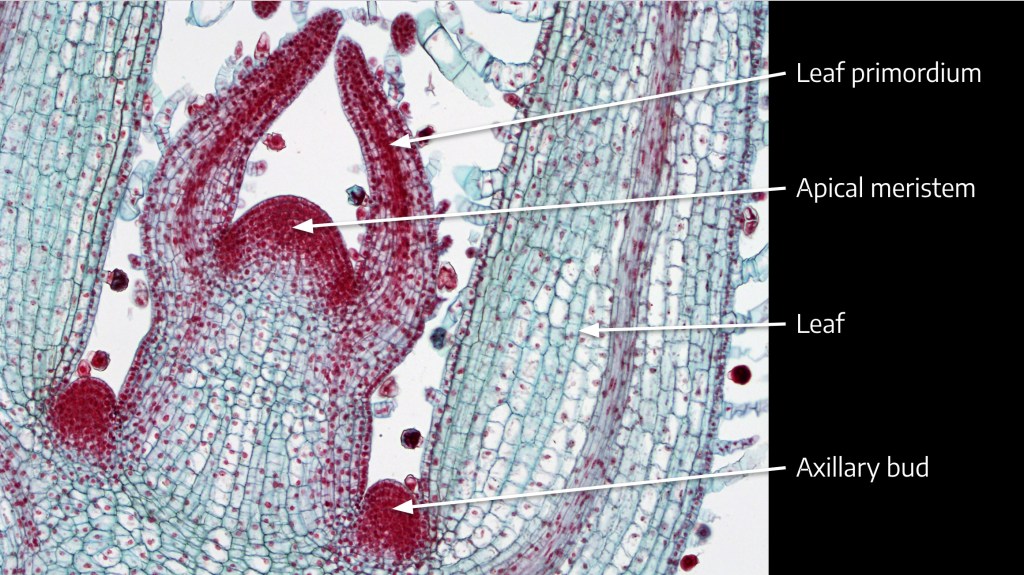

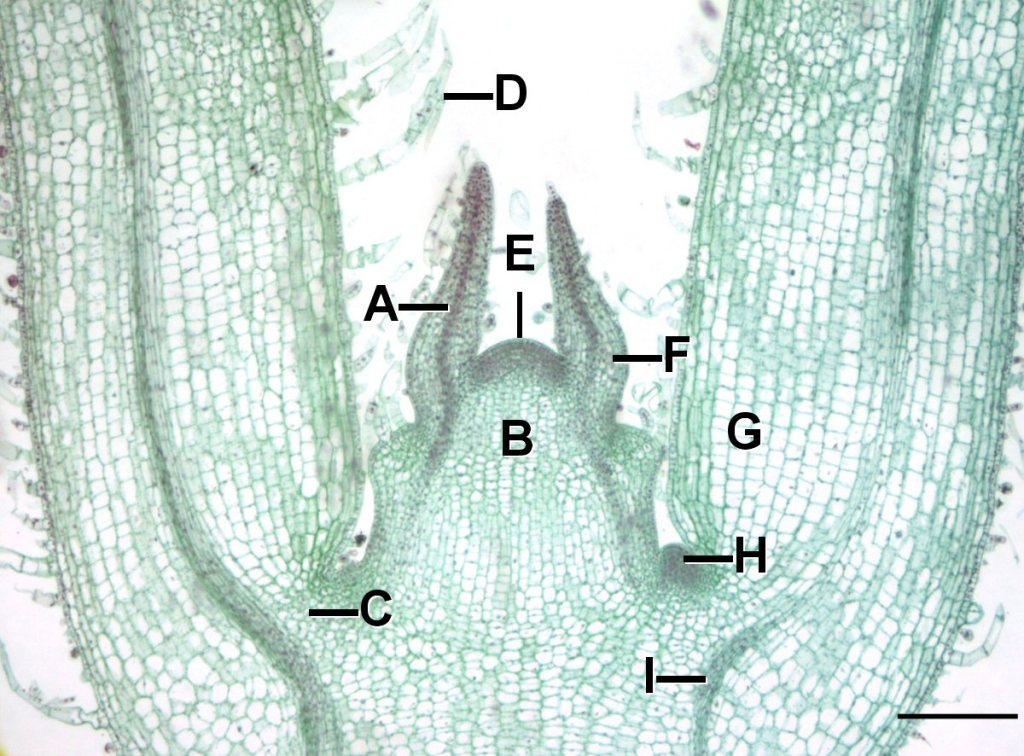

Stem cells are located in the central zone of the meristem (see below), and a small number of stem cells are present in each meristem layer that together forms the central zone of the meristem.

Leaves are initiated at the periphery of the shoot apical meristem (or SAM), see below, as a protruding pool of founder cells, known as leaf primordia, and develop into flat structures of variable sizes and shapes.

Leaves start as simple peg-like outgrowths, but these leaf primordia rapidly grow, change shape and differentiate, ultimately forming the final leaf we are familiar with. Leaves are initiated sequentially in precisely ordered patterns and continue to grow for around six weeks.

Jon Houseman, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Leaf formation occurs in stages. Firstly, the founder cells that are destined to develop into leaves (the incipient primordium) are recruited from the peripheral zone of the SAM. Then, after the initiation of the leaf primordium, and both the upper and lower leaf surfaces, as well as the front and back of the leaf, are established. Next, the leaf blade, or lamina, is initiated at the margin, and finally, growth occurs throughout the entire leaf blade, which expands the leaf in all directions.

Photo by Raymond JC Cannon

Summing up

In conclusion, virtually all of the parts of a mature tree originate from small populations of stem cells that are maintained within meristems. There is a lot more to the whole process, of course, particularly concerning hormones (auxins), which modulate plant growth. It is the accumulation of plant hormones in the shoot apical meristem, that promotes the formation of leaf primordia and thereby initiates leaf formation. There is much more to find out about this extraordinary phenomenon, particularly at the molecular and genetic levels, but as science digs deeper into the process, I am happy to think about it as marvelous and astonishing, even though we are familiar with it. Without it, where would we be?

References

Bar, M., & Ori, N. (2014). Leaf development and morphogenesis. Development, 141(22), 4219-4230.

Du, F., Guan, C., & Jiao, Y. (2018). Molecular mechanisms of leaf morphogenesis. Molecular plant, 11(9), 1117-1134.

Friedman, W. E., Moore, R. C., & Purugganan, M. D. (2004). The evolution of plant development. American Journal of Botany, 91(10), 1726-1741.

Kean-Galeno, T., Lopez-Arredondo, D., & Herrera-Estrella, L. (2024). The shoot apical meristem: an evolutionary molding of higher plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(3), 1519.

Nakayama, H., Koga, H., Long, Y., Hamant, O., & Ferjani, A. (2022). Looking beyond the gene network–metabolic and mechanical cell drivers of leaf morphogenesis. Journal of Cell Science, 135(8), jcs259611.

Singh, M. B., & Bhalla, P. L. (2006). Plant stem cells carve their own niche. Trends in Plant Science, 11(5), 241-246.

Smith, L. G., & Hake, S. (1992). The initiation and determination of leaves. The Plant Cell, 4(9), 1017.

Stahl, Y., & Simon, R. (2005). Plant stem cell niches. The International journal of developmental biology, 49(5-6), 479-489.

Wyka, T. P., Robakowski, P., Żytkowiak, R., & Oleksyn, J. (2022). Anatomical acclimation of mature leaves to increased irradiance in sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus L.). Photosynthesis Research, 154(1), 41-55.

Other related blogs and links.

https://rseco.org/content/712-shoot-apical-meristems.html

https://kids.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frym.2023.965617

This was a fascinating story, with just the right amount of science mixed with wonder. Thank you!

Thank you😁

‘O day and night, but this is wondrous strange!’ –Shakespeare, Hamlet (Act I, Scene 5)

I remember as if it were yesterday how fascinated I was when I heard all this for the first time in my botany and embryology lectures at university. Today, 35 years later, with all the progress we made in genetics and molecular biology, my fascination is even greater. It is hard to imagine where we would be without the miraculous meristems, is it not?

Yes, indeed! Science goes deeper and deeper, but it still remains miraculous, in some ways.😁