Ivy bees (Colletes hederae) are pretty little solitary bees which appear late in the year and forage on ivy (Hedera spp.). There are often dozens of these stripy little mining bees – so called because they nest in the ground, in loose, sandy soil – buzzing around the ivy flowers in September and October. They have furry ginger thoraxes and orange/yellow and black striped abdomens (below).

The ivy bee – or Colletes hederae Schmidt & Westrich, 1993 – to give it its full scientific name, has only been present in the UK for a relatively short period time, being first recorded in Dorset in 2001. So technically, it is a non-native species, but since it arrived here by a natural process of range expansion, it can in no way be considered as anything other than a new, and welcome addition to our insect fauna. Another, interesting thing about this species, is that no-one seems to have noticed it before 1993! See below for an explanation!

In the short period of time since it arrived here – presumably by flying over the Channel – it has ‘colonised’ (not the right word as I discuss below) much of England, and spread north as far as southern Scotland. Oh, and it has also hopped over the Irish Sea to Ireland! Probably stopping off on the Isle of Man on the way?

In this blog, I ask: where did they come from; how did they manage to become so firmly established here in such a short space of time; and, why did no-one notice them before 1993?

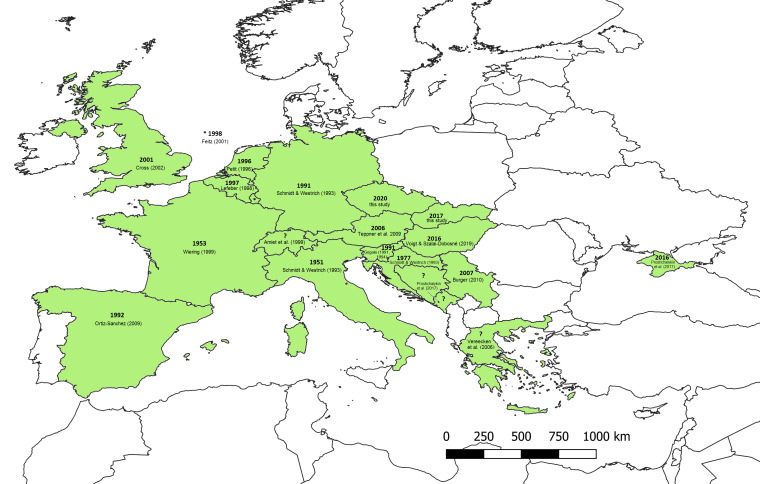

The Ivy bee has been spreading out right across Europe, and has probably not reached the full extent of its potential range (see map, below). It appears to be expanding out in two main directions: firstly, enlarging its area to the northwest (e.g. into the UK and Ireland); and secondly, towards the east, in southern Europe (e.g. from Italy and Croatia to Serbia, Greece, Bosnia and Crimea).

From Bogusch et al. (2021). CC BY 4.0

So, to summarise, Ivy bees are now present in Austria (first discovered in 2006), Belgium, Bosnia, Croatia, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Montenegro, Netherlands, Serbia, Slovenia, Slovakia (first recorded in 2017), Spain, UK and Channel Islands, Switzerland, Russian Crimea and Hungary.

From what I can gather, the spread of the Ivy bee has not been a gradual, incremental increase in its territory, but rather, has been via a series of leaps and bounds, such that there are gaps in the distribution which get filled in at a later date as the species becomes more established (see Bogusch et al., 2021 for a full explanation)

The reasons for these remarkable range expansions are not fully understood, but must have occurred, at least in part, as a result of climate change; particularly warmer autumns. An interesting fact, is that the ivy bee appears to have moved into new areas without being burdened (i.e. accompanied) by its cleptoparasites: the brood parasites or cuckoo bees in the genus Epeolus, which specialise on Colletes species (see photo below). Could this freedom from parasitoids, at least to date, have helped it to expand so quickly? N.B. Cleptoparasitic bees sneak into the nests of their hosts and steal food resources. Presumably, they will catch up with their hosts at some stage in the future?

The Ivy bee was only given its scientific name in 1993 (see Schmidt & Westrich, 1993). It was not a new species in the sense of having just evolved; rather it is a cryptic species which went unnoticed. It was in fact, hiding in plain sight, but unnoticed because nobody distinguished it from other, very similar congeneric or sibling species.

There are three very similar late-flying sibling species: Colletes hederae (Ivy bee), Colletes succinctus (heather bee) and Colletes halophilus (sea aster bee). Both sexes of Colletes hederae are extremely similar to those of C. halophilus, and although ivy bees are, on average, slightly larger than their two close relatives, these species can only be distinguished with confidence by microscopic examination (Benton & Fremlin, 2018). All three species are on the wing in late summer and into autumn, although the Ivy bee probably flies the latest in the year.

Thus, we can conclude that the discovery of the ivy bee was impeded by the fact that people were confusing it with C. succinctus and C. halophilus. I like to think of it as hiding among lookalikes!

So, it was more a case of the species just not being noticed; or more precisely, not being distinguished from other, very similar bees. It that sense it was cryptic, or hidden. It had presumably existed happily for millions of years, but it only came to our attention relatively recently! Like many so-called cryptic species, see here.

Coloniser is, I think, the wrong word to use about the peregrinations of a tiny bee which is such a welcome addition to our fauna! Like the Vikings, they crossed the seas and arrived in new lands! But they didn’t conquer or subjugate any of the native species, as far as I can gather! They are not an invasive, alien species in the sense of a damaging pest.

There is more than enough ivy to go round. At least half the floral resources, i.e. nectar and pollen, are in any case, uncollected by the native flower-visiting insect community in autumn, as researchers at the University of Sussex, discovered (Harris et al., 2023). A large proportion of both the nectar and pollen produced by ivy plants is uncollected by insects, and therefore, effectively wasted. The ivy bees have therefore, joined something of an unfilled niche!

There are, I think nine species of Colletes bees in the UK, and about 60 in Europe, out of an astonishing estimated total of around 700 Colletes species (522 described species), worldwide! They are all ground-nesting bees, solitary in nature but with a propensity to nest close together in aggregations of underground nests, which can number in their thousands. They line their nests with a cellophane-like secretion, a true polyester, which is why they are also called polyester bees. A researcher at Bath University (Rebecca Belisle) found that:

Colletes halophilus nest cell linings are shown to be biocomposite structures constructed from silk fibres laid down as a scaffolding for the application of a copolymer matrix composed of multiple ester containing compounds.

Basically, this lining makes the nests highly robust, strongly resistant to chemical degradation, and biodegradable (Belisle, 2011). Sounds like a very useful polymer!

The best guide to the different species in Britain is the wonderful collection of photographs of Colletes species on Steven Falk’s Flickr website, here.

The other two, similar looking species are Colletes succinctus, which gathers Heather pollen and and C. halophilus which gathers Sea Aster pollen (shown below).

It is fairly easy to identify Ivy Bees on ivy, and to distinguish them from honeybees, even though they are a similar size and both nectar on Ivy flowers in the late summer and autumn. Here are photographs of the two species I took on the same day (below).

There is also a very good guide to Identifying Ivy Bees and Honeybees on the UK Pollinator Monitoring Scheme (PoMS) website here.

The smaller males (see below) emerge before the females and may forage on a variety of species before ivy comes into bloom.

Females, on the other hand, forage largely on Hedera helix, but will collect pollen from a number of different plant species, especially at the beginning of their active period. Nevertheless, pollen analysis from ivy bees collected in Sussex found that ivy pollen accounted for 98.5% of samples, so they were not visiting many other sorts of flowers (Hennessy et al., 2021).

Ivy bee (Colletes hederae) on an ivy leaf

Ivy bees are attracted by the different floral scents emitted by H. helix – they are quite a pungent flower when in bloom – but they also respond to visual cues, despite ivy flowers being relatively inconspicuous, visually, against the bright green leaves (see photo below).

Ivy bees are a welcome addition to the UK fauna, in my opinion. They rarely sting people, and in any case, have a sting that is usually unable to penetrate human skin and only causes minimal pain for a short duration – comparable to that of a nettle sting – according to researchers from the University of Sussex (Hennessy et al., 2020).

Common ivy (Hedera helix L.) is a very common resource and the flowers provide late season pollen and nectar for a host of other insects, including honey bees, bumblebees, wasps, hoverflies, other flies, and butterflies. See previous blog: The ivy league! Insects nectaring on Hedera helix.

Jacobs et al. (2010) considered that Vespula wasps were the most effective pollinators of ivy because they were frequent visitors, had relatively fast foraging rates, and carried a large amount of pollen on their bodies. However, Ivy bees can also carry a lot of pollen (see both images, below), so they must be pretty good pollinators!

Ivy bees appear to transport dry pollen in less dense scopae on their hind-legs (see below), which means that the pollen grains remain viable for cross-pollination. N.B. bumblebees and honeybees often mix pollen with nectar and transport it as a dense, moist clump, which reduces the viability of the pollen (Parker et al., 2015).

In conclusion, the Ivy bee (Colletes hederae) is a particularly pretty little hymenopteran, in my view, with its furry orange thorax, stripy abdomen, and almond-shaped compound eyes. It arrived on a wave of expansion, moving out across Europe from an original stronghold somewhere in Central Europe, around Croatia (Istria), north and central Italy, SW Germany and SE France, according to Petr Bogusch and colleagues (2021). Ivy plants are abundant and there is an excess of nectar and pollen for pollinators which in any case would go wasted if not consumed. However, there remains a certain mystery surrounding its rapid expansion, or can we simply mark it down to the rapidly changing climate?

Links

Steven Falk collection Colletes (plasterer bees): https://www.flickr.com/photos/63075200@N07/collections/72157633396536539/

References

Beckett, O., & Kenny, J. (2022). Ivy Bee (Colletes hederae Schmidt and Westrich)(Hymenoptera, Colletidae), a solitary bee new to Ireland. The Irish Naturalists’ Journal, 39, 88-90.

Belisle, R. A. (2011). Microstructure and Chemical Composition of Colletes halophilus Nest Cell Linings (Doctoral dissertation, University of Bath).

Benton, T., & Fremlin, M. A. R. I. A. (2018). Colletes hederae Schmidt & Westrich, 1993 (the Ivy Bee) in Colchester: some observations on phenology, development and behaviour. Essex Naturalist (New Series), 35, 179-184.

Bischoff, I., Eckelt, E., & Kuhlmann, M. (2005). On the biology of the ivy-bee Colletes hederae Schmidt & Westrich, 1993 (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Bonner Zoologische Beiträge, 53, 27-36.

Bogusch, P., Lukáš, J., Šlachta, M., Straka, J., Šima, P., Erhart, J., & Přidal, A. (2021). The spread of Colletes hederae Schmidt & Westrich, 1993 continues–first records of this plasterer bee species from Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Biodiversity Data Journal, 9.

Carreck, N. L., Andernach, J., Ariss, A., Dowd, H., Gant, A., Garbuzov, M., … & Ratnieks, F. L. (2023). Distribution and abundance of the ivy bee, Colletes hederae Schmidt & Westrich, 1993, in Sussex, southern England. BioInvasions Record, 12(3).

Ferrari, R. R., Onuferko, T. M., Monckton, S. K., & Packer, L. (2020). The evolutionary history of the cellophane bee genus Colletes Latreille (Hymenoptera: Colletidae): molecular phylogeny, biogeography and implications for a global infrageneric classification. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 146, 106750.

Garbuzov, M., & Ratnieks, F. L. (2014). Ivy: an underappreciated key resource to flower‐visiting insects in autumn. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 7(1), 91-102.

Harris, C., Ferguson, H., Millward, E., Ney, P., Sheikh, N., & Ratnieks, F. L. (2023). Phenological imbalance in the supply and demand of floral resources: Half the pollen and nectar produced by the main autumn food source, Hedera helix, is uncollected by insects. Ecological Entomology, 48(3), 371-383.

Hennessy, G., Balfour, N. J., Shackleton, K., Goulson, D., & Ratnieks, F. L. (2020). Stinging risk and sting pain of the ivy bee, Colletes hederae. Journal of Apicultural Research, 59(2), 223-231.

Hennessy, G., Uthoff, C., Abbas, S., Quaradeghini, S. C., Stokes, E., Goulson, D., & Ratnieks, F. L. (2021). Phenology of the specialist bee Colletes hederae and its dependence on Hedera helix L. in comparison to a generalist, Apis mellifera. Arthropod-Plant Interactions, 15, 183-195.

Jacobs, J. H., Clark, S. J., Denholm, I., Goulson, D., Stoate, C., & Osborne, J. L. (2010). Pollinator effectiveness and fruit set in common ivy, Hedera helix (Araliaceae). Arthropod-Plant Interactions, 4, 19-28.

Kuhlmann, M., Else, G. R., Dawson, A., & Quicke, D. L. (2007). Molecular, biogeographical and phenological evidence for the existence of three western European sibling species in the Colletes succinctus group (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Organisms Diversity & Evolution, 7(2), 155-165.

Lukas, K., Dötterl, S., Ayasse, M., & Burger, H. (2023). Colletes hederae bees are equally attracted by visual and olfactory cues of inconspicuous Hedera helix flowers. Chemoecology, 33(5), 135-143.

Onuferko, T. M., Bogusch, P., Ferrari, R. R., & Packer, L. (2019). Phylogeny and biogeography of the cleptoparasitic bee genus Epeolus (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and cophylogenetic analysis with its host bee genus Colletes (Hymenoptera: Colletidae). Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 141, 106603.

Parker, A. J., Tran, J. L., Ison, J. L., Bai, J. D. K., Weis, A. E., & Thomson, J. D. (2015). Pollen packing affects the function of pollen on corbiculate bees but not non-corbiculate bees. Arthropod-Plant Interactions, 9, 197-203.

Ratnieks, F. L., Beckett, O., Nelson, B., & FitzPatrick, Ú. (2022). Distribution and status of the Ivy Bee (Colletes hederae) in Counties Wexford and Wicklow, Ireland, Autumn 2022. The Irish Naturalists’ Journal, 39, 67-75.

Roberts, S., Potts, S., Biesmeijer, K., Kuhlmann, M., Kunin, W., & Ohlemüller, R. (2011). Assessing continental-scale risks for generalist and specialist pollinating bee species under climate change. BioRisk, 6, 1-18.

Schmidt, K., & Westrich, P. (1993). Colletes hederae n. sp., eine bisher unerkannte, auf Efeu (Hedera) spezialisierte Bienenart (Hymenoptera: Apoidea). Entomologische Zeitschrift, 103(6), 89-112.

Teppner, H., & Brosch, U. (2015). Pseudo-oligolecty in Colletes hederae (Apidae-Colletinae, Hymenoptera). Linzer Biologische Beiträge, 47(1), 301-306.

Zenz, K., Zettel, H., Kuhlmann, M., & Krenn, H. W. (2021). Morphology, pollen preferences and DNA-barcoding of five Austrian species in the Colletes succinctus group (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Entomologica Austriaca, 29, 351-368.

Thanks to your post I fell in love with the ivy bees. Let’s hope their cleptoparasites leave them alone for a while. 😊 In the meantime, let’s wait and see which cryptic species will be discovered next. 🤠🔎🐝